Armstrong Siddeley Mamba

| Mamba | |

|---|---|

| |

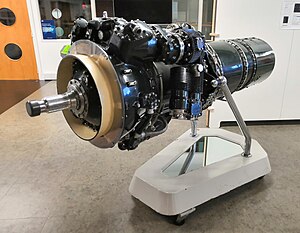

| Mamba engine on display at Sheffield Hallam University | |

| Type | Turboprop |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Armstrong Siddeley |

| First run | April 1946 |

| Major applications | Boulton Paul Balliol A.W. Apollo Short Seamew |

| Developed into | Armstrong Siddeley Double Mamba Armstrong Siddeley Adder |

The Armstrong Siddeley Mamba was a British turboprop engine produced by Armstrong Siddeley in the late 1940s and 1950s, producing around 1,500 effective horsepower (1,100 kW).

Armstrong Siddeley gas turbine engines were named after snakes.

Design and development

[edit]The Mamba was a compact engine [1] with a 10-stage axial compressor, six combustion chambers and a two-stage power turbine. The epicyclic reduction gearbox was incorporated in the propeller spinner. Engine starting was by cartridge. The Ministry of Supply designation was ASMa (Armstrong Siddeley Mamba). The ASMa.3 gave 1,475 ehp and the ASMa.6 was rated at 1,770 ehp. A 500-hour test was undertaken in 1948[1] and the Mamba was the first turboprop engine to power the Douglas DC-3, when in 1949, a Dakota testbed was converted to take two Mambas.

The Mamba was also developed into the form of the Double Mamba, which was used to power the Fairey Gannet anti-submarine aircraft for the Royal Navy. This was essentially two Mambas lying side-by-side and driving contra-rotating propellers separately through a common gearbox.

A turbojet version of the Mamba was developed as the Armstrong Siddeley Adder, by removing the reduction gearbox.[2]

Variants and applications

[edit]

- ASMa.3 Mamba

- [3]

- Armstrong Whitworth Apollo

- Avro Athena

- Boulton Paul Balliol

- Breguet Vultur

- Miles M.69 Marathon II

- Douglas C-47 Dakota

- Short SB.3

- ASMa.5 Mamba

- Development engine for Armstrong Siddeley ASMD.3 Double Mamba[3]

- ASMa.6 Mamba

- [3]

- Short Seamew

- ASMa.7 Mamba

- A version for civil applications[3]

- Swiss-Mamba SM-1 (aft turbofan variant)

- EFW N-20

- Mamba 112

- (ASMa.6)

Engines on display

[edit]Surviving Mambas are on display in the UK at the Midland Air Museum, Coventry Airport, Warwickshire, the Royal Air Force Museum Cosford and the East Midlands Aeropark. Another example is to be found at the Hertha Ayrton STEM Centre at Sheffield Hallam University, UK and a Mamba Mk 110 (serial number 654606 - ZP3043, possibly originally installed in a Short Seamew) is on loan from the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust to BAE Systems at Farnborough Airport, Hampshire.

Overseas, a Swiss-Mamba SM-1 is displayed at the Flieger-Flab-Museum Dübendorf in Swizterland and another Mamba can be seen at the Aviation Heritage Museum (Western Australia).[4]

Specifications (ASMa.6)

[edit]

Data from Aircraft engines of the World 1957[5]

General characteristics

- Type: Turboprop

- Length: 90.2 in (2,290 mm)

- Diameter: 33 in (840 mm)

- Frontal area: 5.9 sq ft (0.55 m2)

- Dry weight: 850 lb (390 kg)

Components

- Compressor: 11 stage axial flow

- Combustors: Annular combustion chamber with 24 vapourising burners

- Turbine: 3 stage axial flow

- Fuel type: Aviation Kerosene / JP-4

Performance

- Maximum power output: 1,650 shp (1,230 kW) plus 320 lbf (1.4 kN) thrust ; 1,770 shp (1,320 kW) (equivalent) at 15,000 rpm

- Overall pressure ratio: 6:1

- Air mass flow: 21.5 lb/s (9.8 kg/s) at 15,000 rpm

- Specific fuel consumption: 0.69 lb/(hp⋅h) (0.42 kg/kWh) (equivalent shaft horsepower)

- Power-to-weight ratio: 2.08 hp/lb (3.42 kW/kg) (equivalent shaft horsepower)

See also

[edit]Related development

Related lists

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Aero Engine Information". RAF Museum. Archived from the original on 16 November 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ Gunston 1989, p.20.

- ^ a b c d Taylor, John W.R. FRHistS. ARAeS (1955). Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1955-56. London: Sampson, Low, Marston & Co Ltd.

- ^ Studio, Cicada. "Armstrong Siddeley Mamba". www.raafawa.org.au. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Wilkinson, Paul H. (1957). Aircraft engines of the World 1957 (15th ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons Ltd. pp. 122–123.

Bibliography

[edit]- "Aero Engines 1954", Flight, www.flightglobal.com, p. 446, 9 April 1954, retrieved 4 November 2008

- Gunston, Bill (1989). World Encyclopaedia of Aero Engines (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Patrick Stephens Limited. ISBN 978-1-85260-163-8.

External links

[edit]- Brossett, Gary. "Armstrong Siddeley Mamba and propeller". enginehistory.org. Archived from the original on 24 December 2005. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "ARMSTRONG SIDDELEY". aoxj32. Archived from the original on 2 July 2006. Retrieved 16 March 2019.