Bender, Moldova

Bender

Tighina[1] | |

|---|---|

Views of Bender

(Very Bottom) Municipality of Bender | |

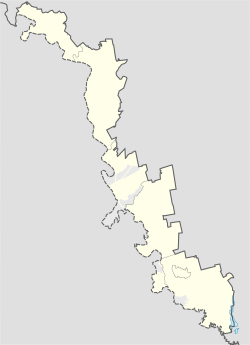

Municipality of Bender (in red) | |

Bender located in Moldova | |

| Coordinates: 46°50′N 29°29′E / 46.833°N 29.483°E | |

| Country (de jure) | |

| Country (de facto) | |

| Founded | 1408 |

| Government | |

| • Head of the State Administration of Bendery | Nikolai Gliga[2] |

| Area | |

• Total | 97.29 km2 (37.56 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 15 m (49 ft) |

| Population (2015) | |

• Total | 91,000 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| Climate | Cfb |

| Website | bendery-ga |

| |

Bender ([benˈder], Moldovan Cyrillic: Бендер) or Bendery (Russian: Бендеры, [bʲɪnˈdɛrɨ]; Ukrainian: Бендери), also known as Tighina (Moldovan Cyrillic: Тигина), is a city within the internationally recognized borders of Moldova under de facto control of the unrecognized Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (Transnistria) (PMR) since 1992. It is located on the western bank of the river Dniester in the historical region of Bessarabia.

Together with its suburb Proteagailovca, the city forms a municipality, which is separate from Transnistria (as an administrative unit of Moldova) according to Moldovan law. Bender is located in the buffer zone established at the end of the 1992 War of Transnistria. While the Joint Control Commission has overriding powers in the city, Transnistria has de facto administrative control.

The fortress of Tighina was one of the important historic fortresses of the Principality of Moldova until 1812.

Name

[edit]First mentioned in 1408 as Tyagyanyakyacha (Old East Slavic: Тягянякяча) in a document in Old Slavonic (the term has Cuman origins[3]), the town was known in the Middle Ages as Tighina in Romanian from Moldavian sources and later as Bender in Ottoman sources. The fortress and the city were called Bender for most of the time they were a rayah of the Ottomans (1538–1812), and during most of the time they belonged to the Russian Empire (1828–1917). They were known as Tighina (Тигина, [tiˈɡina]) in the Principality of Moldavia, in the early part of the Russian Empire period (1812–1828), and during the time the city belonged to Romania (1918–1940; 1941–1944).

The city is part of the historical region of Bessarabia. During the Soviet period the city was known in the Moldavian SSR as Bender in Romanian, written Бендер with the Moldovan Cyrillic alphabet, as Bendery (Бендéры) in Russian and Bendery (Бенде́ри) in Ukrainian. Today the city is officially named Bender, but both Bender and Tighina are in use.[4]

History

[edit]

The town was first mentioned as an important customs post in a commerce grant issued by the Moldavian voivode Alexander the Good to the merchants of Lviv on October 8, 1408. The name "Tighina" is found in documents from the second half of the 15th century. Genoese merchants used to call the town Teghenaccio.[5] The town was the main Moldavian customs point on the commercial road linking the country to the Crimean Khanate.[6] During his reign of Moldavia, Stephen III had a small wooden fort built in the town to defend the settlement from Tatar raids.[7]

In 1538, the Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent conquered the town from Moldavia, and renamed it Bender. Its fortifications were developed into a full fortress under the same name under the supervision of the Turkish architect Koji Mimar Sinan. The Ottomans used it to keep the pressure on Moldavia. At the end of the 16th century several unsuccessful attempts to retake the fortress were made: in the summer of 1574 Prince John III the Terrible led a siege on the fortress, as did Michael the Brave in 1595 and 1600. About the same time the fortress was attacked by Zaporozhian Cossacks.

In the 18th century, the fort's area was expanded and modernized by the prince of Moldavia Antioh Cantemir, who carried out these works under Ottoman supervision.

On the 5th of April 1710 the Bendery Constitution (more commonly known as the Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk) was accepted in Bendery.[8] It established the principle of the separation of powers in government between the legislative, executive, and judiciary branches almost 40 years before the publication of Montesquieu's Spirit of the Laws.

In 1713, the fortress, the town, and the neighboring village Varnița were the site of skirmishes between Charles XII of Sweden, who had taken refuge there with the Cossack Hetman Ivan Mazepa after his defeat in the Battle of Poltava in 1709, and the Turks who wished to enforce the departure of the Swedish king.[9]

During the second half of the 18th century, the fortress fell three times to the Russians during the Russo-Turkish Wars (in 1770, 1789, and in 1806 without a fight).

Along with Bessarabia, the city was annexed to the Russian Empire in 1812, and remained part of the Russian Governorate of Bessarabia until 1917. Many Ukrainians, Russians and Jews settled in or around Bender, and the town quickly became predominantly Russian-speaking. By 1897, speakers of Romanian made up only around 7% of Bender's population, while 33.4% were Jews.[10]

Tighina was part of the Moldavian Democratic Republic in 1917–1918, and after 1918, following the Union of Bessarabia with Romania, the city belonged to the Kingdom of Romania, where it was the seat of Tighina County. In 1918, it was shortly controlled by the Odesa Soviet Republic which was driven out by the Romanian army. The local population was critical of Romanian authorities; pro-Soviet separatism remained popular.[11] On Easter Day, 1919, the bridge over the Dniester River was blown up by the French Army in order to block the Bolsheviks from coming to the city.[1] In the same year, there was a pro-Soviet uprising in Bender, attempting to attach the city to the newly founded Soviet Union. Several hundred communist workers and Red Army members from Bessarabia, headed by Grigori Stary, seized control in Bender on May 27. However, the uprising was crushed on the same day by the Romanian army.

Romania launched a policy of Romanianization and the use of Russian was now discouraged and in certain cases restricted. In Bender, however, Russian continued to be the city's most widely spoken language, being native to 53% of its residents in 1930. Although their share had doubled, Romanian-speakers made up only 15%.[12]

Along with Bessarabia, the city was occupied by the Soviet Union on June 28, 1940, following an ultimatum. In the course of World War II, it was retaken by Romania in July 1941 (under which a treaty regarding the occupation of Transnistria was signed a month later), and again by the USSR in August 1944. Most of the city's Jews were killed during the Holocaust, although Bender continued to have a significant Jewish community until most emigrated after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

In 1940–1941 and from 1944 to 1991 it was one of the four "republican cities", not subordinated to a district, of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, one of the 15 republics of the Soviet Union. Since 1991, the city has been disputed between the Republic of Moldova and Transnistria. Due to the city's key strategic location on the right bank of the Dniester river, 10 km (6 mi) from left-bank Tiraspol, Bender saw the heaviest fighting of the 1992 War of Transnistria during the Battle of Bender. Since then, it is controlled by Transnistrian authorities, although it has been formally in the demilitarized zone established at the end of the conflict.

Moldovan authorities control the commune of Varnița, a suburb fringing the city to the north. Transnistrian authorities control the suburban communes of Proteagailovca, which borders the city to the west and Gîsca, which borders the city to the south-west. They also control Chițcani and Cremenciug, further to the south-east, while Moldovans are in control of Copanca, further to the south-east.

Gallery

[edit]-

City centre

-

The historical military cemetery in the city

-

Bender Railway Station

-

Bender Fortress

-

Horse and carriage at Bender Fortress

-

Soviet-era memorial with flower bed, Bender

-

Downtown fountain, Bender

-

Transnistrian crest on plinth, Bender

Administration

[edit]Nikolai Gliga is the head of the state administration of Bender as of 2015[update].

List of Heads of the state administration of Bender

[edit]- Tom Zenovich (1995 ~ October 30, 2001[13])

- Aleksandr Posudnevsky (October 30, 2001[14] ~ January 11, 2007[15])

- Vyacheslav Kogut (January 11, 2007[16] ~ January 5, 2012)

- Aleksandr Moskalyov, acting Head of Administration (January 5, 2012[17] ~ February 9, 2012)

- Valery Kernichuk (February 9, 2012[18] ~ November 15, 2012[19])

- Yuriy Gervazyuk (January 24, 2013[20] ~ March 18, 2015)

- Lada Delibalt (March 20, 2015[21] ~ April 7, 2015[22])

- Nikolai Gliga (April 7, 2015[2] ~ )

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Bendery (1991-2021) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

3.9 (39.0) |

9.5 (49.1) |

16.3 (61.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.4 (79.5) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

22.4 (72.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

8.9 (48.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

15.6 (60.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.6 (29.1) |

0.3 (32.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

5.9 (42.6) |

0.8 (33.4) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −4.6 (23.7) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

0.6 (33.1) |

6.1 (43.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.6 (65.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

7.5 (45.5) |

3.1 (37.6) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 39 (1.5) |

29 (1.1) |

35 (1.4) |

44 (1.7) |

48 (1.9) |

66 (2.6) |

48 (1.9) |

41 (1.6) |

45 (1.8) |

38 (1.5) |

36 (1.4) |

37 (1.5) |

506 (19.9) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 77 | 70 | 65 | 59 | 58 | 57 | 54 | 61 | 71 | 80 | 80 | 68 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 86.8 | 87.6 | 136.4 | 198 | 275.9 | 306 | 328.6 | 319.3 | 249 | 189.1 | 84 | 68.2 | 2,328.9 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 2.8 | 3.1 | 4.4 | 6.6 | 8.9 | 10.2 | 10.6 | 10.3 | 8.3 | 6.1 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 6.4 |

| Source: CLIMATE-DATA[23] Weather2visit(Sun)[24] | |||||||||||||

People and culture

[edit]Demographics

[edit]In 1920, the population of Bender was approximately 26,000. At that time, one third of the population was Jewish. One third of the population was Romanian. Germans, Russians, and Bulgarians were also mixed into the population during that time.[1]

At the 2004 Census, the city had a population of 100,169, of which the city itself 97,027, and the commune of Proteagailovca, 3,142.[25]

| Ethnic composition | |||||||||

| Ethnic group | 1930 census | 1959 census | 1970 census | 1979 census | 1989 census | 2004 census[25] | |||

| the city itself |

Proteagailovca | The municipality |

% | ||||||

| Russians | 15,116 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 57,800 | 41,949 | 1,482 | 43,431 | 43.35% |

| Moldovans1 | - | N/A | N/A | N/A | 41,400 | 24,313 | 756 | 25,069 | 25.03% |

| Romanians1 | 5,464 | N/A | N/A | N/A | - | 61 | 0-5 | 61-66 | 0.06% |

| Ukrainians2 | - | N/A | N/A | N/A | 25,100 | 17,348 | 658 | 18,006 | 17.98% |

| Ruthenians2 | 1,349 | N/A | N/A | N/A | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bulgarians | 170 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3,800 | 3,001 | 163 | 3,164 | 3.16% |

| Gagauzians | 40 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1,600 | 1,066 | 25 | 1,091 | 1.09% |

| Jews | 8,279 | N/A | N/A | N/A | - | 383 | 2 | 385 | 0.38% |

| Germans | 243 | N/A | N/A | - | - | 258 | 6 | 264 | 0.26% |

| Poles | 309 | N/A | N/A | N/A | - | 190 | 0-12 | 190-202 | 0.20% |

| Armenians | 46 | N/A | N/A | N/A | - | 173 | 0-16 | 173-189 | 0.18% |

| Roma | 24 | N/A | N/A | N/A | - | 132 | 0-5 | 132-137 | 0.13% |

| Belarusians | 188 | N/A | N/A | N/A | - | 713 | 19 | 732 | 0.73% |

| others | N/A | N/A | N/A | 8,300 | 7,440 | 0-31 | 7,440-7,471 | 7.44% | |

| non-declared | 51 | N/A | N/A | - | N/A | ||||

| Greeks | 37 | N/A | N/A | - | N/A | ||||

| Hungarians | 24 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Serbs, Croats, Slovenes | 22 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Czechs, Slovaks | 19 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Turks | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Albanians | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Total | 31,384[26] | 43,000 | 72,300 | 101,292[27] | 138,000[28] | 97,027[29] | 3,142[29] | 100,169 | 100% |

Note: 1 Since the independence of Moldova, there has been ongoing controversy over whether Romanians and Moldovans should be counted officially as the same ethnic group or not. At the census, every citizen could only declare one nationality. Consequently, one could not declare oneself both Moldovan and Romanian.

Note: 2 The Ukrainian population of Bessarabia was counted in the past as "Ruthenians"

| Native language | ||

| Language | 1930 census | 2004 census |

| Russian | 16,566 | N/A |

| Yiddish | 8,117 | N/A |

| Romanian | 4,718 | N/A |

| Ukrainian | 1,286 | N/A |

| German | 225 | N/A |

| Polish | 219 | N/A |

| Bulgarian | 78 | N/A |

| Turkish | 26 | N/A |

| Greek | 21 | N/A |

| Hungarian | 20 | N/A |

| Romani languages | 16 | N/A |

| Czech, Slovak | 14 | N/A |

| Armenian | 11 | N/A |

| Serbo-Croatian, Slovene | 8 | N/A |

| Albanian | 2 | N/A |

| other | 11 | N/A |

| non-declared | 46 | N/A |

| Total | 31,384[26] | 100,169 |

Population dynamics by years: [30] [31]

Media

[edit]- Radio Chișinău 106.1 FM

Notable people

[edit]

- Mehmed Selim Pasha (1771 in Bender – 1831 in Damascus) nickname: "Benderli" was an Ottoman statesman and Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire 1824/28

- Lev Berg (1876 in Bender – 1950 in Leningrad), a leading Jewish Russian geographer, biologist and ichthyologist

- Boris Solotareff (1889 in Bender – 1966 in New York) was a Russian painter. His work was in the mainstream of Eastern European Expressionism, with influences of Art Deco from the time when he lived in Paris

- Jerzy Neyman (1894 in Bendery – 1981) was a Polish mathematician and statistician

- Baruch Agadati (1895 in Bendery – 1976 in Israel) was a Russian Empire-born Israeli classical ballet dancer, choreographer, painter, and film producer and director

- Sir Michael Postan FBA (1899 in Bendery – 1981 in Cambridge), a British historian

- Yosef Kushnir (born 1900 in Bender - 1983 in Israel) was an Israeli politician who served in the Knesset

- Maurice Raizman (1905 in Bendery – 1974 in Paris) was a French chess master.

- Yevgeny Fyodorov (1910 in Bendery - 1981) was a Soviet geophysicist, statesman, public figure and academician

- Zrubavel Gilad (1912 in Bender - 1988 in Israel) was a Hebrew poet, editor and translator

- Yaakov Yardaur (born 1912 in Bender - died 1997 in Israel - Lehi militant

- Tamara Buciuceanu (born 1929 in Tighina - 2019 in Bucharest) a Romanian stage, screen and TV personality

- Ilarion Ciobanu (1931 in Ciucur, Tighina – 2008 in Bucharest) was a Romanian actor

- Emil Constantinescu (born 1939 in Tighina) a Romanian professor and politician, who served as the third President of Romania, from 1996 to 2000.

- Viktor Sokolov (born 1962 in Bender), admiral and commander of the Russian Black Sea Fleet

- Petro Poroshenko (born 1965) is the fifth President of Ukraine. He spent his childhood and youth in Bendery where his father Oleksiy was heading a machine building plant

- Vadim Krasnoselsky (born 1970) is a Transnistrian politician who was elected president in 2016. He has lived in Bender beginning with the age of 8 years, when his father was transferred to a local military base in 1978.

- Nicolai Lilin (born 1980) is an Italian-Moldovan writer famous for writing Siberian Education, a fake memoir which narrated his youth in Bender.

- Ilie Cazac (born 1985 in Tighina), a former Moldovan tax inspector and political prisoner.

Sport

[edit]- Veaceslav Semionov (born 1956 in Bender) is a Moldavian football manager and former footballer. Since November 2014 he is the head coach of Moldavian football club FC Dacia Chișinău

- Fedosei Ciumacenco (born 1973 in Bendery) is an Olympian Moldovan race walker, competed in the 20 kilometres distance at the Summer olympics: 1996, 2000, 2004 and 2008

- Serghei Stolearenco (born 1978 in Bender), a Moldovan former sprint freestyle swimmer, competed in the men's 50 m freestyle at the 2000 Summer Olympics

- Alexandru Melenciuc (born 1979 in Bender) is a Moldovan footballer. He currently plays for Navbahor Namangan

- Andrei Tcaciuc (born 1982 in Bender) is a Moldavian football midfielder who plays for FC Speranța Crihana Veche

- Igor Bugaiov (born 1984 in Bendery), a footballer, who plays for FC Irtysh Pavlodar

- Alexei Casian (born 1987 in Bender), a Moldavian football midfielder who represents Lane Xang Intra F.C.

- Vadim Cemîrtan (born 1987 in Tighina), a Moldovan football striker who plays for FC Bunyodkor

- Artyom Khachaturov (born 1992 in Bender) is an Armenian-Moldovan footballer who currently plays for Moldovan club FC Zimbru Chișinău

Sport

[edit]FC Dinamo Bender is the city's professional football club, formerly playing in the top Moldovan football league, the Divizia Națională, before being relegated.

International relations

[edit]Twin towns – Sister cities

[edit]Bender is twinned with:

Beira, Mozambique

Beira, Mozambique Cavriago, Italy

Cavriago, Italy Dubăsari, Moldova

Dubăsari, Moldova Montesilvano, Italy

Montesilvano, Italy Ochamchire, Georgia

Ochamchire, Georgia

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Transnistria's political status is disputed. It considers itself to be an independent state, but this is not recognised by any UN member state. The Moldovan government and the international community consider Transnistria a part of Moldova's territory.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Kaba, John (1919). Politico-economic Review of Basarabia. United States: American Relief Administration. pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b "Указ Президента ПМР №139 "О временно исполняющем обязанности главы государственной администрации города Бендеры"". Официальный сайт Президента ПМР.

- ^ History of Bender on the Official website of Republic of Moldova Archived March 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine: "trecătoare" înseamnă în limba cumană Tighina

- ^ (in Romanian) "Cetatea Tighina" Archived April 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine on Monument.md

- ^ Poștarencu, D. Din istoria Tighinei, 1992, p. 84.

- ^ Ion Nistor, Istoria Basarabiei, Cernăuți, 1923, reprint Chișinău, Cartea Moldovenească, 1991, p.76

- ^ "Bender fortress" Archived February 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine on Moldova.md

- ^ "The First Constitution of Ukraine (5 April 1710)", Harvard Ukrainian Studies

- ^ Charles XII of Sweden first took refuge in a Moldavian house in the town, then moved to a house specially built for him in Varnița. cf. Ion Nistor, Ibidem, p.140

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly - Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on April 21, 2014.

- ^ "Turism istoric: Tighina sub epoleti". formula-as.ro.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ (in Russian) Olvia Press News Agency Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Russian) Olvia Press News Agency Archived October 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Russian) REGNUM News Agency

- ^ (in Russian) Official website of the Supreme Council of Transnistria

- ^ (in Russian) Transnistrian News Portal Pridnestrovets.RF Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Russian) Official website of the President of Transnistria

- ^ Указ Президента ПМР №754 Archived November 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Указ Президента ПМР №14 "О назначении главы государственной администрации города Бендеры"". Официальный сайт Президента ПМР.

- ^ "Указ Президента ПМР № 120 "О временно исполняющем обязанности главы государственной администрации города Бендеры"". Официальный сайт Президента ПМР.

- ^ "Указ Президента ПМР №138 "О прекращении исполнения обязанностей главы государственной администрации города Бендеры"". Официальный сайт Президента ПМР.

- ^ "BENDER WEATHER BY MONTH // WEATHER AVERAGES". Climate data. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ "Bender monthly weather averages". weather 2 visit. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ a b The Transnistrian census of 2004 data by nationality at http://pop-stat.mashke.org/pmr-ethnic-loc2004.htm

- ^ a b 1930 Romanian Census data for the Tighina County Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Moldova". citypopulation.de.

- ^ Marian Enache, Dorin Cimpoesu, Misiune Diplomatica in Republica Moldova (Iași: Polirom, 2000), p. 399

- ^ a b "pridnestrovie.net". Archived from the original on March 18, 2009.

- ^ "Moldovan towns based on a censuses of 1897—2015" (in Russian). Archived from the original on July 19, 2017.

- ^ "State administration of Bendery report for 2019 19.9 Mb" (in Russian). Archived from the original on April 1, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

External links

[edit]- (in Polish) Bendery (Bender) in the Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland (1880)

- City portal