Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton | |

|---|---|

Stanton, c. 1880, age 65 | |

| Born | Elizabeth Smith Cady November 12, 1815 Johnstown, New York, U.S. |

| Died | October 26, 1902 (aged 86) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Cemetery, New York City, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 7, including Theodore and Harriot |

| Parent(s) | Daniel Cady Margaret Livingston |

| Relatives | James Livingston (grandfather) Gerrit Smith (cousin) Elizabeth Smith Miller (cousin) Nora Stanton Barney (granddaughter) |

| Signature | |

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (née Cady; November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, the first convention to be called for the sole purpose of discussing women's rights, and was the primary author of its Declaration of Sentiments. Her demand for women's right to vote generated a controversy at the convention but quickly became a central tenet of the women's movement.[1] She was also active in other social reform activities, especially abolitionism.

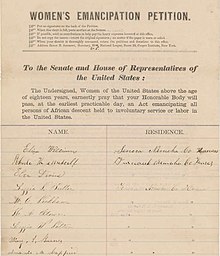

In 1851, she met Susan B. Anthony and formed a decades-long partnership that was crucial to the development of the women's rights movement. During the American Civil War, they established the Women's Loyal National League to campaign for the abolition of slavery, and they led it in the largest petition drive in U.S. history up to that time. They started a newspaper called The Revolution in 1868 to work for women's rights.

After the war, Stanton and Anthony were the main organizers of the American Equal Rights Association, which campaigned for equal rights for both African Americans and women, especially the right of suffrage. When the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was introduced that would provide suffrage for black men only, they opposed it, insisting that suffrage should be extended to all African Americans and all women at the same time. Others in the movement supported the amendment, resulting in a split. During the bitter arguments that led up to the split, Stanton sometimes expressed her ideas in elitist and racially condescending language. In her opposition to the voting rights of African Americans Stanton was quoted to have said, "It becomes a serious question whether we had better stand aside and let 'Sambo' walk into the kingdom first." [2] Frederick Douglass, an abolitionist friend who had escaped from slavery, reproached her for such remarks.

Stanton became the president of the National Woman Suffrage Association, which she and Anthony created to represent their wing of the movement. When the split was healed more than twenty years later, Stanton became the first president of the united organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association. This was largely an honorary position; Stanton continued to work on a wide range of women's rights issues despite the organization's increasingly tight focus on women's right to vote.

Stanton was the primary author of the first three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage, a massive effort to record the history of the movement, focusing largely on her wing of it. She was also the primary author of The Woman's Bible, a critical examination of the Bible that is based on the premise that its attitude toward women reflects prejudice from a less civilized age.

Childhood and family background

[edit]Elizabeth Cady was born into the leading family of Johnstown, New York. Their family mansion on the town's main square was handled by as many as twelve servants. Her conservative father, Daniel Cady, was one of the richest landowners in the state. A member of the Federalist Party, he was an attorney who served one term in the U.S. Congress and became a justice in the New York Supreme Court.[3]

Her mother, Margaret Cady (née Livingston), was more progressive, supporting the radical Garrisonian wing of the abolitionist movement and signing a petition for women's suffrage in 1867. She was described, at least earlier in her life, as "[n]early six feet tall, strong willed and self-reliant, ... She was the only person in the household not in awe of her husband who was 12 years her senior."[4]

Elizabeth was the seventh of eleven children, six of whom died before reaching full adulthood, including all of the boys. Her mother, exhausted by giving birth to so many children and the anguish of seeing so many of them die, became withdrawn and depressed. Tryphena, the oldest daughter, together with her husband Edward Bayard, assumed much of the responsibility for raising the younger children.[5]

In her memoir, Eighty Years & More, Stanton said there were three African-American manservants in her household when she was young. Researchers have determined that one of them, Peter Teabout, was a slave and probably remained so until all enslaved people in New York state were freed on July 4, 1827. Stanton recalled him fondly, saying that she and her sisters attended the Episcopal church with Teabout and sat with him in the back of the church rather than in front with the white families.[6][7]

Education and intellectual development

[edit]Stanton received a better education than most women of her era. She attended Johnstown Academy in her hometown until the age of 15. The only girl in its advanced classes in mathematics and languages, she won second prize in the school's Greek competition and became a skilled debater. She enjoyed her years at the school and said she did not encounter any barriers there due to her gender.[8][9]

She was made sharply aware of society's low expectations for women when Eleazar, her last surviving brother, died at the age of 20 just after graduating from Union College in Schenectady, New York. Her father and mother were incapacitated by grief. The ten-year-old Stanton tried to comfort her father, saying she would try to be all her brother had been. Her father said, "Oh my daughter, I wish you were a boy!"[10][9]

Stanton had many educational opportunities as a young child. Their neighbor, Reverend Simon Hosack, taught her Greek and mathematics. Edward Bayard, her brother-in-law and Eleazar's former classmate at Union College, taught her philosophy and horsemanship. Her father brought her law books to study so she could participate in debates with his law clerks at the dinner table. She wanted to go to college, but no colleges at that time accepted female students. Moreover, her father initially decided she did not need further education. He eventually agreed to enroll her in the Troy Female Seminary in Troy, New York, which was founded and run by Emma Willard.[9]

In her memoirs, Stanton said that during her student days in Troy she was greatly disturbed by a six-week religious revival conducted by Charles Grandison Finney, an evangelical preacher and a central figure in the revivalist movement. His preaching, combined with the Calvinistic Presbyterianism of her childhood, terrified her with the possibility of her own damnation: "Fear of judgment seized my soul. Visions of the lost haunted my dreams. Mental anguish prostrated my health."[11] Stanton credited her father and brother-in-law with convincing her to disregard Finney's warnings. She said they took her on a six-week trip to Niagara Falls during which she read works of rational philosophers who restored her reason and sense of balance. Lori D. Ginzberg, one of Stanton's biographers, says there are problems with this story. For one thing, Finney did not preach for six weeks in Troy while Stanton was there. Ginzberg suspects that Stanton embellished a childhood memory to underline her belief that women harm themselves by falling under the spell of religion.[12]

Marriage and family

[edit]

As a young woman, Stanton traveled often to the home of her cousin, Gerrit Smith, who also lived in upstate New York. His views were very different from those of her conservative father. Smith was an abolitionist and a member of the "Secret Six," a group of men who financed John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in an effort to spark an armed uprising of enslaved African Americans.[13] At Smith's home, where she spent summers and was considered "part of the family,"[14] she met Henry Brewster Stanton, a prominent abolitionist agent. Despite her father's reservations, the couple married in 1840, omitting the word "obey" from the marriage ceremony. Stanton later wrote, "I obstinately refused to obey one with whom I supposed I was entering into an equal relation."[15] While uncommon, this practice was not unheard of; Quakers had been omitting "obey" from the marriage ceremony for some time.[16] Stanton took her husband's surname as part of her own, signing herself Elizabeth Cady Stanton or E. Cady Stanton, but not Mrs. Henry B. Stanton.[citation needed]

Soon after returning from their European honeymoon, the Stantons moved into the Cady household in Johnstown. Henry Stanton studied law under his father-in-law until 1843, when the Stantons moved to Boston (Chelsea), Massachusetts, where Henry joined a law firm. While living in Boston, Elizabeth enjoyed the social, political, and intellectual stimulation that came with a constant round of abolitionist gatherings. Here, she was influenced by such people as Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison and Ralph Waldo Emerson.[17] In 1847, the Stantons moved to Seneca Falls, New York, in the Finger Lakes region. Their house, which is now a part of the Women's Rights National Historical Park, was purchased for them by Elizabeth's father.[18]

The couple had seven children. At that time, child-bearing was considered to be a subject that should be handled with great delicacy. Stanton took a different approach, raising a flag in front of her house after giving birth, a red flag for a boy and a white one for a girl.[19] One of her daughters, Harriot Stanton Blatch, became, like her mother, a leader of the women's suffrage movement. Because of the spacing of their children's births, one historian has concluded that the Stantons must have used birth control methods. Stanton herself said her children were conceived by what she called "voluntary motherhood." In an era when it was commonly held that a wife must submit to her husband's sexual demands, Stanton believed that women should have command over their sexual relationships and childbearing.[20] She also said, however, that "a healthy woman has as much passion as a man."[21]

Stanton encouraged both her sons and daughters to pursue a broad range of interests, activities, and learning.[22] She was remembered by her daughter Margaret as being "cheerful, sunny and indulgent."[23] She enjoyed motherhood and running a large household, but she found herself unsatisfied and even depressed by the lack of intellectual companionship and stimulation in Seneca Falls.[24]

During the 1850s, Henry's work as a lawyer and politician kept him away from home for nearly 10 months out of every year. This frustrated Elizabeth when the children were small because it made it difficult for her to travel.[25] The pattern continued in later years, with husband and wife living apart more often than together, maintaining separate households for several years. Their marriage, which lasted 47 years, ended with Henry Stanton's death in 1887.[26]

Both Henry and Elizabeth were staunch abolitionists, but Henry, like Elizabeth's father, disagreed with the idea of female suffrage.[27] One biographer described Henry as, "at best a halfhearted 'women's rights man.'"[28]

Early activism

[edit]World Anti-Slavery Convention

[edit]

While on their honeymoon in England in 1840, the Stantons attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. Elizabeth was appalled by the convention's male delegates, who voted to prevent women from participating even if they had been appointed as delegates of their respective abolitionist societies. The men required the women to sit in a separate section, hidden by curtains from the convention's proceedings. William Lloyd Garrison, a prominent American abolitionist and supporter of women's rights who arrived after the vote had been taken, refused to sit with the men and sat with the women instead.[29]

Lucretia Mott, a Quaker minister, abolitionist and women's rights advocate, was one of the women who had been sent as a delegate. Although Mott was much older than Stanton, they quickly bonded in an enduring friendship, with Stanton eagerly learning from the more experienced activist. While in London, Stanton heard Mott preach in a Unitarian chapel, the first time Stanton had heard a woman give a sermon or even speak in public.[30] Stanton later gave credit to this convention for focusing her interests on women's rights.[31]

Seneca Falls Convention

[edit]An accumulation of experiences was having an effect on Stanton. The London convention had been a turning point in her life. Her study of law books had convinced her that legal changes were necessary to overcome gender inequities. She had personal experience of the stultifying role of women as wives and housekeepers. She said, "the wearied, anxious look of the majority of women, impressed me with a strong feeling that some active measures should be taken to remedy the wrongs of society in general, and of women in particular."[32] This knowledge, however, did not immediately lead to action. Relatively isolated from other social reformers and fully occupied with household duties, she was at a loss as to how she could engage in social reform.[citation needed]

In the summer of 1848, Lucretia Mott traveled from Pennsylvania to attend a Quaker meeting near the Stanton's home. Stanton was invited to visit with Mott and three other progressive Quaker women. Finding herself in sympathetic company, Stanton said she poured out her "long-accumulating discontent, with such vehemence and indignation that I stirred myself, as well as the rest of the party, to do and dare anything."[32] The gathered women agreed to organize a women's rights convention in Seneca Falls a few days later, while Mott was still in the area.[33]

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpation on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her… He has not ever permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise. He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice.

Stanton was the primary author of the convention's Declaration of Rights and Sentiments,[34] which was modeled on the U.S. Declaration of Independence. Its list of grievances included the wrongful denial of women's right to vote, signaling Stanton's intent to generate a discussion of women's suffrage at the convention. This was a highly controversial idea at the time but not an entirely new one. Her cousin Gerrit Smith, no stranger to radical ideas himself, had called for women's suffrage shortly before at the Liberty League convention in Buffalo. When Henry Stanton saw the inclusion of women's suffrage in the document, he told his wife that she was acting in a way that would turn the proceedings into a farce. Lucretia Mott, the main speaker, was also disturbed by the proposal.[35]

An estimated 300 women and men attended the two-day Seneca Falls Convention.[36] In her first address to a large audience, Stanton explained the purpose of the gathering and the importance of women's rights. Following a speech by Mott, Stanton read the Declaration of Sentiments, which the attendees were invited to sign.[37] Next came the resolutions, all of which the convention adopted unanimously except for the ninth, which read, "it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves the sacred right of the elective franchise."[38] Following a vigorous debate, this resolution was adopted only after Frederick Douglass, an abolitionist leader who had formerly been enslaved, gave it his strong support.[39]

Stanton's sister Harriet attended the convention and signed its Declaration of Sentiments. Her husband, however, made her remove her signature.[40]

Although this was a local convention organized on short notice, its controversial nature ensured that it was widely noted in the press, with articles appearing in newspapers in New York City, Philadelphia and many other places.[41] The Seneca Falls Convention is now recognized as an historic event, the first convention to be called for the purpose of discussing women's rights. The convention's Declaration of Sentiments became "the single most important factor in spreading news of the women's rights movement around the country in 1848 and into the future," according to Judith Wellman, a historian of the convention.[42] The convention initiated the use of women's rights conventions as organizing tools for the early women's movement. By the time of the second National Women's Rights Convention in 1851, the demand for women's right to vote had become a central tenet of the United States women's rights movement.[43]

A Rochester Women's Rights Convention was held in Rochester, New York two weeks later, organized by local women who had attended the one in Seneca Falls. Both Stanton and Mott spoke at this convention. The convention in Seneca Falls had been chaired by James Mott, the husband of Lucretia Mott. The Rochester convention was chaired by a woman, Abigail Bush, another historic first. Many people were disturbed by the idea of a woman chairing a convention of both men and women. How, for example, might people react if a woman ruled a man out of order? Stanton herself spoke in opposition to the election of a woman as the chair of this convention, although she later acknowledged her mistake and apologized for her action.[44]

When the first National Women's Rights Convention was organized in 1850, Stanton was unable to attend because she was pregnant. Instead, she sent a letter to the convention entitled "Should women hold office" that outlined the movement's goals.[45] The letter emphatically endorsed women's right to hold office, stating that "women might have a 'purifying, elevating, softening influence' on the 'political experiment of our Republic.'”[45] Thereafter it became a tradition to open national women's rights conventions with a letter by Stanton, who did not participate in person in a national convention until 1860.[46]

Partnership with Susan B. Anthony

[edit]While visiting Seneca Falls in 1851, Susan B. Anthony was introduced to Stanton by Amelia Bloomer, a mutual friend and a supporter of women's rights. Anthony, who was five years younger than Stanton, came from a Quaker family that was active in reform movements. Anthony and Stanton soon became close friends and co-workers, forming a relationship that was a turning point in their lives and of great importance to the women's movement.[47]

The two women had complementary skills. Anthony excelled at organizing, while Stanton had an aptitude for intellectual matters and writing. Stanton later said, "In writing we did better work together than either could alone. While she is slow and analytical in composition, I am rapid and synthetic. I am the better writer, she the better critic."[48] Anthony deferred to Stanton in many ways throughout their years of work together, not accepting an office in any organization that would place her above Stanton.[49] In their letters, they referred to one another as "Susan" and "Mrs. Stanton."[50]

Because Stanton was homebound with seven children while Anthony was unmarried and free to travel, Anthony assisted Stanton by supervising her children while Stanton wrote. Among other things, this allowed Stanton to write speeches for Anthony to give.[51] One of Anthony's biographers said, "Susan became one of the family and was almost another mother to Mrs. Stanton's children."[52] One of Stanton's biographers said, "Stanton provided the ideas, rhetoric, and strategy; Anthony delivered the speeches, circulated petitions, and rented the halls. Anthony prodded and Stanton produced."[51] Stanton's husband said, "Susan stirred the puddings, Elizabeth stirred up Susan, and then Susan stirs up the world!"[51] Stanton herself said, "I forged the thunderbolts, she fired them."[53] By 1854, Anthony and Stanton "had perfected a collaboration that made the New York State movement the most sophisticated in the country," according to Ann D. Gordon, a professor of women's history.[54]

After the Stantons moved from Seneca Falls to New York City in 1861, a room was set aside for Anthony in every house they lived in. One of Stanton's biographers estimated that, over her lifetime, Stanton spent more time with Anthony than with any other adult, including her own husband.[55]

In December 1865, Stanton and Anthony submitted the first women's suffrage petition directed to Congress during the drafting of the Fourteenth Amendment.[45] The women challenged the use of the word "male" in the version submitted to the States for ratification.[45] When Congress failed to remove the language, Stanton announced her candidacy as the first woman to run for Congress in October 1866.[45] She ran as an independent and secured only 24 votes, but her candidacy sparked conversations surrounding women's officeholding separate from suffrage.[45]

In December 1872, Stanton and Anthony each wrote New Departure memorials to Congress and were invited to read their memorials to the Senate Judiciary Committee.[45] This further brought women's suffrage and officeholding to the forefront of Congress's agenda, even though the New Departure agenda was ultimately rejected.[45]

The relationship was not without its strains, especially as Anthony could not match Stanton's charm and charisma. In 1871, Anthony said, "whoever goes into a parlor or before an audience with that woman does it at the cost of a fearful overshadowing, a price which I have paid for the last ten years, and that cheerfully, because I felt that our cause was most profited by her being seen and heard, and my best work was making the way clear for her."[56]

Temperance activity

[edit]Excessive consumption of alcohol was a severe social problem during this period, one that began to diminish only in the 1850s.[57] Many activists considered temperance to be a women's rights issue because of laws that gave husbands complete control of the family and its finances. The law provided almost no recourse to a woman with a drunken husband, even if his condition left the family destitute and he was abusive to her and their children. If she managed to obtain a divorce, which was difficult to do, he could easily end up with sole guardianship of their children.[58]

In 1852, Anthony was elected as a delegate to the New York state temperance convention. When she tried to participate in the discussion, the chairman stopped her, saying that women delegates were there only to listen and learn. Years later, Anthony observed, "No advanced step taken by women has been so bitterly contested as that of speaking in public. For nothing which they have attempted, not even to secure the suffrage, have they been so abused, condemned and antagonized."[59] Anthony and other women walked out and announced their intention to organize a women's temperance convention. Later that year, about five hundred women met in Rochester and created the Women's State Temperance Society, with Stanton as president and Anthony as state agent.[60] This leadership arrangement, with Stanton in the public role as president and Anthony as the energetic force behind the scenes, was characteristic of the organizations they founded in later years.[61]

In her first public speech since 1848, Stanton delivered the convention's keynote address, one that antagonized religious conservatives. She called for drunkenness to be legal grounds for divorce at a time when many conservatives opposed divorce for any reason. She appealed for wives of drunkard husbands to take control of their marital relations, saying, "Let no woman remain in relation of wife with the confirmed drunkard. Let no drunkard be the father of her children."[62] She attacked the religious establishment, calling for women to donate their money to the poor instead of to the "education of young men for the ministry, for the building up a theological aristocracy and gorgeous temples to the unknown God."[63]

At the organization's convention the following year, conservatives voted Stanton out as president, whereupon she and Anthony resigned from the organization.[64] Temperance was not a significant reform activity for Stanton afterwards, although she continued to use local temperance societies in the early 1850s as conduits for advocating women's rights.[65] She regularly wrote articles for The Lily, a monthly temperance newspaper that she helped transform into one that reported news of the women's rights movement.[66] She also wrote for The Una, a women's rights periodical edited by Paulina Wright Davis, and for the New York Tribune, a daily newspaper edited by Horace Greeley.[67]

Married Women's Property Act

[edit]The status of married women at that time was in part set by English common law which for centuries had set the doctrine of coverture in local courts. It held wives were under the protection and control of their husbands.[68] In the words of William Blackstone's 1769 book Commentaries on the Laws of England : "By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage."[69] The husband of a married woman became the owner of any property she brought into a marriage. She could not sign contracts, operate a business in her own name, or retain custody of their children in the event of a divorce.[70][68] In practice some American courts followed the common law. Some Southern states like Texas and Florida provided more equality for women. Across the country state legislatures were taking control away from common law traditions by passing legislation.[71]

In 1836, the New York legislature began considering a Married Women's Property Act, with women's rights advocate Ernestine Rose an early supporter who circulated petitions in its favor.[72] Stanton's father supported this reform. Having no sons to pass his considerable wealth to, he was faced with the prospect of having it eventually pass to the control of his daughters' husbands. Stanton circulated petitions and lobbied legislators in favor of the proposed law as early as 1843.[73]

The law eventually passed in 1848. It allowed a married woman to retain the property that she possessed before the marriage or acquired during the marriage, and it protected her property from her husband's creditors.[74] Enacted shortly before the Seneca Falls Convention, it strengthened the women's rights movement by increasing the ability of women to act independently.[75] By weakening the traditional belief that husbands spoke for their wives, it assisted many of the reforms that Stanton championed, such as the right of women to speak in public and to vote.[citation needed]

In 1853, Susan B. Anthony organized a petition campaign in New York state for an improved property rights law for married women.[76] As part of the presentation of these petitions to the legislature, Stanton spoke in 1854 to a joint session of the Judiciary Committee, arguing that voting rights were needed to enable women to protect their newly won property rights.[77] In 1860, Stanton spoke again to the Judiciary Committee, this time before a large audience in the assembly chamber, arguing that women's suffrage was the only real protection for married women, their children and their material assets.[75] She pointed to similarities in the legal status of woman and slaves, saying, "The prejudice against color, of which we hear so much, is no stronger than that against sex. It is produced by the same cause, and manifested very much in the same way. The negro's skin and the woman's sex are both prima facie evidence that they were intended to be in subjection to the white Saxon man."[78] The legislature passed the improved law in 1860.[citation needed]

Dress reform

[edit]

In 1851, Elizabeth Smith Miller, Stanton's cousin, brought a new style of dress to the upstate New York area. Unlike traditional floor-length dresses, it consisted of pantaloons worn under a knee-length dress. Amelia Bloomer, Stanton's friend and neighbor, publicized the attire in The Lily, a monthly magazine that she published. Thereafter it was popularly known as the "Bloomer" dress, or just "Bloomers." It was soon adopted by many female reform activists despite harsh ridicule from traditionalists, who considered the idea of women wearing any sort of trousers as a threat to the social order. To Stanton, it solved the problem of climbing stairs with a baby in one hand, a candle in the other, and somehow also lifting the skirt of a long dress to avoid tripping. Stanton wore "Bloomers" for two years, abandoning the attire only after it became clear that the controversy it created was distracting people from the campaign for women's rights. Other women's rights activists eventually did the same.[79]

Divorce reform

[edit]Stanton had already antagonized traditionalists in 1852 at the women's temperance convention by advocating a woman's right to divorce a drunken husband. In an hour-long speech at the Tenth National Women's Rights Convention in 1860, she went further, generating a heated debate that took up an entire session.[80] She cited tragic examples of unhealthy marriages, suggesting that some marriages amounted to "legalized prostitution."[81] She challenged both the sentimental and the religious views of marriage, defining marriage as a civil contract subject to the same restrictions of any other contract. If a marriage did not produce the expected happiness, she said, then it would be a duty to end it.[82] Strong opposition to her speech was voiced in the ensuing discussion. Abolitionist leader Wendell Phillips, arguing that divorce was not a women's rights issue because it affected both women and men equally, said the subject was out of order and tried unsuccessfully to have it removed from the record.[80]

In later years on the lecture circuit, Stanton's speech on divorce was one of her most popular, drawing audiences of up to 1200 people.[83] In an 1890 essay entitled "Divorce versus Domestic Warfare," Stanton opposed calls by some women activists for stricter divorce laws, saying, "The rapidly increasing number of divorces, far from showing a lower state of morals, proves exactly the reverse. Woman is in a transition period from slavery to freedom, and she will not accept the conditions and married life that she has heretofore meekly endured."[84]

Abolitionist activity

[edit]In 1860 Stanton published a pamphlet called The Slaves Appeal written from what she imagined to be the viewpoint of a female slave.[85] The fictional speaker uses vivid religious language ("Men and women of New York, the God of thunder speaks through you")[86] that expresses religious views very different from those that Stanton herself held. The speaker describes the horrors of slavery, saying, "The trembling girl for whom thou didst pay a price but yesterday in a New Orleans market, is not thy lawful wife. Foul and damning, both to the master and the slave, is this wholesale violation of the immutable laws of God."[86] The pamphlet called for defiance of the Federal Fugitive Slave Act, and it included petitions to be used for opposing the practice of hunting escaped slaves.[85]

In 1861, Anthony organized a tour of abolitionist lecturers in upstate New York that included Stanton and several other speakers. The tour began in January just after South Carolina had seceded from the union but before other states had seceded and before the outbreak of war. In her speech, Stanton said that South Carolina was like a willful son whose behavior jeopardized the whole family and that the best course of action was to let it secede. The lecture meetings were repeatedly disrupted by mobs operating under the belief that abolitionist activity was causing southern states to secede. Stanton was not able to participate in some of the lectures because she had to return home to her children.[87] At her husband's urging, she left the lecture tour because of the persistent threat of violence.[88]

Women's Loyal National League

[edit]

In 1863, Anthony moved into the Stantons' house in New York City and the two women began organizing the Women's Loyal National League to campaign for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would abolish slavery. Stanton became president of the new organization and Anthony was secretary.[89] It was the first national women's political organization in the United States.[90] In the largest petition drive in the nation's history up to that time, the League collected nearly 400,000 signatures to abolish slavery, representing approximately one out of every twenty-four adults in the Northern states.[91] The petition drive significantly assisted the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery.[92] The League disbanded in 1864 after it became clear that the amendment would be approved.[93]

Although its purpose was the abolition of slavery, the League made it clear that it also stood for political equality for women, approving a resolution at its founding convention that called for equal rights for all citizens regardless of race or sex.[94] The League indirectly advanced the cause of women's rights in several ways. Stanton pointedly reminded the public that petitioning was the only political tool available to women at a time when only men were allowed to vote.[95] The success of the League's petition drive demonstrated the value of formal organization to the women's movement, which had traditionally resisted being anything other than loosely organized up to that point.[96] Its 5000 members constituted a widespread network of women activists who gained experience that helped create a pool of talent for future forms of social activism, including suffrage.[97] Stanton and Anthony emerged from this endeavor with significant national reputations.[89]

American Equal Rights Association

[edit]After the Civil War, Stanton and Anthony became alarmed at reports that the proposed Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which would provide citizenship for African Americans, would also for the first time introduce the word "male" into the constitution. Stanton said, "if that word 'male' be inserted, it will take us a century at least to get it out."[98]

Organizing opposition to this development required preparation because the women's movement had become largely inactive during the Civil War. In January 1866, Stanton and Anthony sent out petitions calling for a constitutional amendment providing for women's suffrage, with Stanton's name at the top of the list of signatures.[99][100] Stanton and Anthony organized the Eleventh National Women's Rights Convention in May 1866, the first since the Civil War began.[101] The convention voted to transform itself into the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), whose purpose was to campaign for the equal rights of all citizens regardless of race or sex, especially the right of suffrage.[102] Stanton was offered the post of president but declined in a favor of Lucretia Mott. Other officers included Stanton as first vice president, Anthony as a corresponding secretary, Frederick Douglass as a vice president, and Lucy Stone as a member of the executive committee.[103] Stanton provided hospitality for some of the attendees at this convention. Sojourner Truth, an abolitionist and women's rights activist who had formerly been enslaved, stayed at Stanton's house[104] as, of course, did Anthony.[citation needed]

Leading abolitionists opposed the AERA's drive for universal suffrage. Horace Greeley, a prominent newspaper editor, told Anthony and Stanton, "This is a critical period for the Republican Party and the life of our Nation... I conjure you to remember that this is 'the negro's hour.'"[105] Abolitionist leaders Wendell Phillips and Theodore Tilton arranged a meeting with Stanton and Anthony, trying to convince them that the time had not yet come for women's suffrage, that they should campaign for voting rights for black men only, not for all African Americans and all women. The two women rejected this guidance and continued to work for universal suffrage.[106]

In 1866, Stanton declared herself a candidate for Congress, the first woman to do so. She said that although she could not vote, there was nothing in the Constitution to prevent her from running for Congress. Running as an independent against both the Democrat and Republican candidates, she received only 24 votes. Her campaign was noted by newspapers as far away as New Orleans.[107]

In 1867, the AERA campaigned in Kansas for referendums that would enfranchise both African Americans and women. Wendell Phillips, who opposed mixing those two causes, blocked the funding that the AERA had expected for their campaign.[108] By the end of summer, the AERA campaign had almost collapsed, and its finances were exhausted. Anthony and Stanton created a storm of controversy by accepting help during the last days of the campaign from George Francis Train, a wealthy businessman who supported women's rights. Train antagonized many activists by attacking the Republican Party and openly disparaging the integrity and intelligence of African Americans.[109] There is reason to believe that Stanton and Anthony hoped to draw the volatile Train away from his cruder forms of racism, and that he had actually begun to do so.[110] In any case, Stanton said she would accept support from the devil himself if he supported women's suffrage.[111]

After the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, a sharp dispute erupted within the AERA over the proposed Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which would prohibit the denial of suffrage because of race. Stanton and Anthony opposed the amendment, which would have the effect of enfranchising black men, insisting that all women and all African Americans should be enfranchised at the same time. Stanton argued in the pages of The Revolution that by effectively enfranchising all men while excluding all women, the amendment would create an "aristocracy of sex," giving constitutional authority to the idea that men were superior to women.[112] Lucy Stone, who was emerging as a leader of those who were opposed to Stanton and Anthony, argued that suffrage for women would be more beneficial to the country than suffrage for black men but supported the amendment, saying, "I will be thankful in my soul if any body can get out of the terrible pit."[113]

During the debate over the Fifteenth Amendment, Stanton wrote articles for The Revolution with language that was elitist and racially condescending.[114] She believed that a long process of education would be needed before many of the former slaves and immigrant workers would be able to participate meaningfully as voters.[115] Stanton wrote, "American women of wealth, education, virtue and refinement, if you do not wish the lower orders of Chinese, Africans, Germans and Irish, with their low ideas of womanhood to make laws for you and your daughters ... demand that women too shall be represented in government."[116] In another article, Stanton objected to laws being made for women by "Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Yung Tung who do not know the difference between a Monarchy and a Republic."[117] She also used the term "Sambo" on other occasions, drawing a rebuke from her old friend Frederick Douglass.[118]

Douglass strongly supported women's suffrage but said that suffrage for African Americans was a more urgent issue, literally a matter of life and death.[119] He said that white women already exerted a positive influence on government through the voting power of their husbands, fathers and brothers, and that it "does not seem generous" for Anthony and Stanton to insist that black men should not achieve suffrage unless women achieved it at the same time.[120] Sojourner Truth, on the other hand, supported Stanton's position, saying, "if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, you see the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before."[121]

Early in 1869, Stanton called for a Sixteenth Amendment that would provide suffrage for women, saying, "The male element is a destructive force, stern, selfish, aggrandizing, loving war, violence, conquest, acquisition … in the dethronement of woman we have let loose the elements of violence and ruin that she only has the power to curb."[122]

The AERA increasingly divided into two wings, each advocating universal suffrage but with different approaches. One wing, whose leading figure was Lucy Stone, was willing for black men to achieve suffrage first and wanted to maintain close ties with the Republican Party and the abolitionist movement. The other, whose leading figures were Stanton and Anthony, insisted that all women and all African Americans should be enfranchised at the same time and worked toward a women's movement that would no longer be tied to the Republican Party or be financially dependent on abolitionists. The AERA effectively dissolved after an acrimonious meeting in May 1869, and two competing woman suffrage organizations were created in its aftermath.[123] In the words of one of Stanton's biographers, one consequence of the split for Stanton was that, "Old friends became either enemies, like Lucy Stone, or wary associates, as in the case of Frederick Douglass."[124]

The Revolution

[edit]The establishing of woman on her rightful throne is the greatest revolution the world has ever known or ever will know"[125]

In 1868, Anthony and Stanton began publishing a sixteen-page weekly newspaper called The Revolution in New York City. Stanton was co-editor along with Parker Pillsbury, an experienced editor who was an abolitionist and a supporter of women's rights. Anthony, the owner, managed the business aspects of the paper. Initial funding was provided by George Francis Train, the controversial businessman who supported women's rights but who alienated many activists with his political and racial views. The newspaper focused primarily on women's rights, especially suffrage for women, but it also covered topics such as politics, the labor movement and finance. One of its stated goals was to provide a forum in which women could exchange opinions on key issues.[126] Its motto was "Men, their rights and nothing more: women, their rights and nothing less."[127]

Sisters Harriet Beecher Stowe and Isabella Beecher Hooker offered to provide funding for the newspaper if its name was changed to something less inflammatory, but Stanton declined their offer, strongly favoring its existing name.[128]

Their goal was to grow The Revolution into a daily paper with its own printing press, all owned and operated by women.[129] The funding that Train had arranged for the newspaper, however, was less than expected. Moreover, Train sailed for England after The Revolution published its first issue and was soon jailed for supporting Irish independence.[130] Train's financial support eventually disappeared entirely. After twenty-nine months, mounting debts forced the transfer of the paper to a wealthy women's rights activist who gave it a less radical tone.[126] Despite the relatively short time it was in their hands, The Revolution gave Stanton and Anthony a means for expressing their views during the developing split within the women's movement. It also helped them promote their wing of the movement, which eventually became a separate organization.[131]

Stanton refused to take responsibility for the $10,000 debt the newspaper had accumulated, saying she had children to support. Anthony, who had less money than Stanton, took responsibility for the debt, repaying it over a six-year period through paid speaking tours.[132]

National Woman Suffrage Association

[edit]

In May 1869, two days after the final AERA convention, Stanton, Anthony and others formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), with Stanton as president. Six months later, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe and others formed the rival American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which was larger and better funded.[133] The immediate cause for the split in the women's suffrage movement was the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, but the two organizations had other differences as well. The NWSA was politically independent while the AWSA aimed for close ties with the Republican Party, hoping that ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment would lead to Republican support for women's suffrage. The NWSA focused primarily on winning suffrage at the national level while the AWSA pursued a state-by-state strategy. The NWSA initially worked on a wider range of women's issues than the AWSA, including divorce reform and equal pay for women.[134]

As the new organization was being formed, Stanton proposed to limit its membership to women, but her proposal was not accepted. In practice, however, the overwhelming majority of its members and officers were women.[135]

Stanton disliked many aspects of organizational work because it interfered with her ability to study, think, and write. She begged Anthony, without success, to arrange the NWSA's first convention so that she herself would not need to attend. For the rest of her life, Stanton attended conventions only reluctantly if at all, wanting to maintain the freedom to express her opinions without worrying about who in the organization might be offended.[136][137] Of the fifteen NWSA meetings between 1870 and 1879, Stanton presided at four and was present at only one other, leaving Anthony effectively in charge of the organization.[138]

In 1869 Francis and Virginia Minor, husband and wife suffragists from Missouri, developed a strategy based on the idea that the U.S. Constitution implicitly enfranchised women.[139] It relied heavily on the Fourteenth Amendment, which says, "No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States … nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." In 1871 the NWSA officially adopted what had become known as the New Departure strategy, encouraging women to attempt to vote and to file lawsuits if denied that right. Soon hundreds of women tried to vote in dozens of localities.[140] Susan B. Anthony actually succeeded in voting in 1872, for which she was arrested and found guilty in a widely publicized trial.[141] In 1880, Stanton also tried to vote. When the election officials refused to let her place her ballot in the box, she threw it at them.[142] When the Supreme Court ruled in 1875 in Minor v. Happersett that "the Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon anyone,"[141] the NWSA decided to pursue the far more difficult strategy of campaigning for a constitutional amendment that would guarantee voting rights for women.[citation needed]

In 1878, Stanton and Anthony convinced Senator Aaron A. Sargent to introduce into Congress a women's suffrage amendment that, more than forty years later, would be ratified as the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Its text is identical to that of the Fifteenth Amendment except that it prohibits the denial of suffrage because of sex rather than "race, color, or previous condition of servitude."[143]

Stanton traveled with her daughter Harriet to Europe in May 1882 and did not return for a year and a half. Already a public figure of some prominence in Europe, she gave several speeches there and wrote reports for American newspapers. She visited her son Theodore in France, where she met her first grandchild, and traveled to England for Harriet's marriage to an Englishman. After Anthony joined her in England in March 1883, they traveled together to meet with leaders of European women's movements, laying the groundwork for an international women's organization. Stanton and Anthony returned to the U.S. together in November 1883.[144] Hosted by the NWSA, delegates from fifty-three women's organizations in nine countries met in Washington in 1888 to form the organization that Stanton and Anthony had been working toward, the International Council of Women (ICW), which is still active.[145]

Stanton traveled again to Europe in October 1886, visiting her children in France and England. She returned to the U.S. in March 1888 barely in time to deliver a major speech at the founding meeting of the ICW.[146] When Anthony discovered that Stanton had not yet written her speech, she insisted that Stanton stay in her hotel room until she had written it, and she placed a younger colleague outside her door to make sure she did so.[147] Stanton later teased Anthony, saying, "Well, as all women are supposed to be under the thumb of some man, I prefer a tyrant of my own sex, so I shall not deny the patent fact of my subjection."[148] The convention succeeded in bringing increased publicity and respectability to the women's movement, especially when President Grover Cleveland honored the delegates by inviting them to a reception at the White House.[149]

Despite her record of racially insensitive remarks and occasional appeals to the racial prejudices of white people, Stanton applauded the marriage in 1884 of her friend Frederick Douglass to Helen Pitts, a white woman, a marriage that enraged racists. Stanton wrote Douglass a warm letter of congratulation, to which Douglass responded that he had been sure that she would be happy for him. When Anthony realized that Stanton was planning to publish her letter, she convinced her not to do so, wanting to avoid associating women's suffrage with an unrelated and divisive issue.[150]

History of Woman Suffrage

[edit]In 1876, Anthony moved into Stanton's house in New Jersey to begin working with Stanton on the History of Woman Suffrage. She brought with her several trunks and boxes of letters, newspaper clippings, and other documents.[151] Originally envisioned as a modest publication that could be produced quickly, the history evolved into a six-volume work of more than 5700 pages written over a period of 41 years.[citation needed]

The first three volumes, which cover the movement up to 1885, were produced by Stanton, Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage. Anthony handled the production details and the correspondence with contributors. Stanton wrote most of the first three volumes, with Gage writing three chapters of the first volume and Stanton writing the rest.[152] Gage was forced to abandon the project afterwards because of the illness of her husband.[153] After Stanton's death, Anthony published Volume 4 with the help of Ida Husted Harper. After Anthony's death, Harper completed the last two volumes, which brought the history up to 1920.[citation needed]

Stanton and Anthony encouraged their rival Lucy Stone to assist with the work, or at least to send material that could be used by someone else to write the history of her wing of the movement, but she refused to cooperate in any way. Stanton's daughter Harriot Stanton Blatch, who had returned from Europe to assist with the editing, insisted that the history would not be taken seriously if Stone and the AWSA were not included. She herself wrote a 120-page chapter on Stone and the AWSA, which appears in Volume 2.[154]

The History of Woman Suffrage preserves an enormous amount of material that might have been lost forever. Written by leaders of one wing of the divided women's movement it does not, however, give a balanced view of events where their rivals are concerned. It overstates the role of Stanton and Anthony, and it understates or ignores the roles of Stone and other activists who did not fit into the historical narrative they had developed. Because it was for years the main source of documentation about the suffrage movement, historians have had to uncover other sources to provide a more balanced view.[155][156]

Lecture circuit

[edit]Stanton worked as a lecturer for the New York bureau of the Redpath Lyceum from late 1869 until 1879. This organization was part of the Lyceum movement, which arranged for speakers and entertainers to tour the country, often visiting small communities where educational opportunities and theaters were scarce. For ten years, Stanton traveled eight months of the year on the lecture circuit, usually delivering one lecture per day, two on Sundays. She also arranged smaller meetings with local women who were interested in women's rights. Traveling was sometimes difficult. One year, when deep snow closed the railroads, Stanton hired a sleigh and kept going, bundled in furs to protect against freezing weather.[157] During 1871, she and Anthony traveled together for three months through several western states, eventually arriving in California.[158]

Her most popular lecture, "Our Girls," urged young women to be independent and to seek self-fulfillment. In "The Antagonism of Sex," she addressed the question of women's rights with a special fervor. Other popular lectures were "Our Boys," "Co-education," "Marriage and Divorce" and "The Subjugation of Women." On Sundays she would often speak on "Famous Women in the Bible" and "The Bible and Women's Rights."[157]

Her earnings were impressive. During her first three months on the road, Stanton reported, she cleared "$2000 above all expenses … besides stirring women generally up to rebellion."[159] Accounting for inflation, that would be about $63,100 in today's dollars. Because her husband's income had always been erratic and he had invested it badly, the money she earned was welcome, especially with most of their children either in college or soon to begin.[157]

Family events

[edit]

After 15 years in Seneca Falls, Stanton moved to New York City in 1862 when her husband secured the position of deputy collector for the Port of New York. Their son Neil, who worked for Henry as his clerk, was caught taking bribes, causing both father and son to lose their jobs. Henry worked intermittently afterward as a journalist and a lawyer.[160]

When her father died in 1859, Stanton received an inheritance worth an estimated $50,000, or about $1,700,000 in today's dollars.[161] In 1868, she bought a substantial country house near Tenafly, New Jersey, an hour's ride by train from New York City. The Stanton house in Tenafly is now a National Historic Landmark. Henry remained in the city in a rented apartment.[162] Aside from visits, she and Henry afterward mostly lived apart.[citation needed]

Six of the seven Stanton children graduated from college. Colleges were closed to women when Stanton sought higher education, but both of her daughters were educated at Vassar College. Because graduate studies were not yet available to women in the U.S., Harriet enrolled in a master's program in France, which she abandoned after she became engaged to be married. Harriet earned a master's degree from Vassar at the age of 35.[163]

After 1884, Henry began to spend more time at Tenafly. In 1885, just before his 80th birthday, he published a short autobiography called Random Recollections. In it, he said that he had married the daughter of the famous Judge Cady, but he did not provide her name. In the third edition of his book, he mentioned his wife by name a single time.[164] He died in 1887 while she was in England visiting their daughter.[165]

National American Woman Suffrage Association

[edit]The Fifteenth Amendment was ratified in 1870, removing much of the original reason for the split in the women's suffrage movement. As early as 1875, Anthony began urging the NWSA to focus more tightly on women's suffrage instead of a variety of women's issues, which brought it closer to the AWSA's approach.[166] The rivalry between the two organizations remained bitter, however, as the AWSA began to decline in strength during the 1880s.[167]

In the late 1880s, Alice Stone Blackwell, daughter of AWSA leader Lucy Stone, began working to heal the breach among the older generation of leaders.[168] Anthony warily cooperated with this effort, but Stanton did not, disappointed that both organizations wanted to focus almost exclusively on suffrage. She wrote to a friend: "Lucy & Susan alike see suffrage only. They do not see women's religious & social bondage, neither do the young women in either association, hence they may as well combine."[169]

In 1890, the two organizations merged as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). At Anthony's insistence, Stanton accepted its presidency despite her unease at the direction of the new organization. In her speech at the founding convention, she urged it to work on a broad range of women's issues and called for it to include all races, creeds and classes, including "Mormon, Indian and black women."[170] The day after she was elected president, Stanton sailed to her daughter's home in England, where she stayed for eighteen months, leaving Anthony effectively in charge. When Stanton declined reelection to the presidency at the 1892 convention, Anthony was elected to that post.[171]

In 1892, Stanton delivered the speech that became known as The Solitude of Self three different times in as many days, twice to Congressional committees and once as her final address to the NAWSA.[172] She considered it her best speech, and many others agreed. Lucy Stone printed it in its entirety in the Woman's Journal in the space where her own speech normally would have appeared. In pursuit of her lifelong quest to overturn the belief that women were lesser beings than men and therefore not suited for independence, Stanton said in this speech that women must develop themselves, acquiring an education and nourishing an inner strength, a belief in themselves. Self-sovereignty was the essential element in a woman's life, not her role as daughter, wife or mother. Stanton said, "no matter how much women prefer to lean, to be protected and supported, nor how much men desire to have them do so, they must make the voyage of life alone."[173][174]

The Woman's Bible and views on religion

[edit]Stanton said she had been terrified as a child by a minister's talk of damnation, but, after overcoming those fears with the help of her father and brother-in-law, had rejected that type of religion entirely. As an adult, her religious views continued to evolve. While living in Boston in the 1840s, she was attracted to the preaching of Theodore Parker, who, like her cousin Gerritt Smith, was a member of the Secret Six, a group of men who financed John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in an effort to spark an armed slave rebellion. Parker was a transcendentalist and a prominent Unitarian minister who taught that the Bible need not be taken literally, that God need not be envisioned as a male, and that individual men and women had the ability to determine religious truth for themselves.[175]

In the Declaration of Sentiments written for the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, Stanton listed a series of grievances against males who, among other things, excluded women from the ministry and other leading roles in religion. In one of those grievances, Stanton said that man "has usurped the prerogative of Jehovah himself, claiming it as his right to assign for her a sphere of action, when that belongs to her conscience and her God."[176] This was the only grievance that was not a matter of fact (such as exclusion of women from colleges, from the right to vote, etc.), but one of belief, one that challenged a fundamental basis of authority and autonomy.[177]

The years after the Civil War saw a significant increase in the variety of women's social reform organizations and the number of activists in them.[178] Stanton was uneasy about the belief held by many of these activists that government should enforce Christian ethics through such actions as teaching the Bible in public schools and strengthening Sunday closing laws.[179] In her speech at the 1890 unity convention that established the NAWSA, Stanton said, "I hope this convention will declare that the Woman Suffrage Association is opposed to all Union of Church and State and pledges itself … to maintain the secular nature of our government.[180]

Do all you can, no matter what, to get people to think on your reform, and then, if the reform is good, it will come about in due season.[181]

In 1895, Stanton published The Woman's Bible, a provocative examination of the Bible that questioned its status as the word of God and attacked the way it was being used to relegate women to an inferior status. Stanton wrote most of it, with the assistance of several other women, including Matilda Joslyn Gage, who had assisted with the History of Woman Suffrage. In it, Stanton methodically worked her way through the Bible, quoting selected passages and commenting on them, often sarcastically. A best-seller, with seven printings in six months, it was translated into several languages. A second volume was published in 1898.[182]

The book created a storm of controversy that affected the entire women's rights movement. Stanton could not have been surprised, having earlier told an acquaintance, "Well, if we who do see the absurdities of the old superstitions never unveil them to others, how is the world to make any progress in the theologies? I am in the sunset of life, and I feel it to be my special mission to tell people what they are not prepared to hear."[183]

The process of critically examining the text of the Bible, known as historical criticism, was already an established practice in scholarly circles. What Stanton did that was new was to scrutinize the Bible from a woman's point of view, basing her findings on the proposition that much of its text reflected not the word of God but prejudice against women during a less civilized age.[184]

In her book, Stanton explicitly denied much of what was central to traditional Christianity, saying, "I do not believe that any man ever saw or talked with God, I do not believe that God inspired the Mosaic code, or told the historians what they say he did about woman, for all the religions on the face of the earth degrade her, and so long as woman accepts the position that they assign her, her emancipation is impossible."[185] In the book's closing words, Stanton expressed the hope for reconstructing "a more rational religion for the nineteenth century, and thus escape all the perplexities of the Jewish mythology as of no more importance than those of the Greek, Persian, and Egyptian."[186]

At the 1896 NAWSA convention, Rachel Foster Avery, a rising young leader, harshly attacked The Woman's Bible, calling it a "volume with a pretentious title … without either scholarship or literary merit."[187] Avery introduced a resolution to distance the organization from Stanton's book. Despite Anthony's strong objection that such a move was unnecessary and hurtful, the resolution passed by a vote of 53 to 41. Stanton told Anthony that she should resign from her leadership post in protest, but Anthony refused.[188] Stanton afterward grew increasingly alienated from the suffrage movement.[189] The incident led many of the younger suffrage leaders to hold Stanton in low regard for the rest of her life.[190]

Final years

[edit]When Stanton returned from her final trip to Europe in 1891, she moved in with two of her unmarried children who shared a home in New York City.[191] She increased her advocacy of "educated suffrage," something she had long promoted. In 1894, she debated William Lloyd Garrison Jr. on this issue in the pages of Woman's Journal. Her daughter Harriot Stanton Blatch, who was then active in the women's suffrage movement in Britain and would later be a leading figure in the U.S. movement, was disturbed by the views that Stanton expressed during this debate. She published a critique of her mother's views, saying there were many people who had not enjoyed the opportunity to acquire an education and yet were intelligent and accomplished citizens who deserved the right to vote.[192] In a letter to the 1902 NAWSA convention, Stanton continued her campaign, calling for "a constitutional amendment requiring an educational qualification" and saying that "everyone who votes should read and write the English language intelligently."[193]

I am opposed to the domination of one sex over the other. It cultivates arrogance in the one, and destroys the self-respect in the other. I am opposed to the admission of another man, either foreign or native, to the polling-booth, until woman, the greatest factor in civilization, is first enfranchised. An aristocracy of men, composed of all types, shades and degrees of intelligence and ignorance, is not the most desirable substratum for government. To subject intelligent, highly educated, virtuous, honorable women to the behests of such an aristocracy is the height of cruelty and injustice.

In her later years, Stanton became interested in efforts to create cooperative communities and workplaces. She was also attracted to various forms of political radicalism, applauding the Populist movement and identifying herself with socialism, especially Fabianism, a gradualist form of democratic socialism.[195]

In 1898, Stanton published her memoirs, Eighty Years and More, in which she presented the image of herself by which she wished to be remembered. In it, she minimized political and personal conflicts and omitted any discussion of the split in the women's movement. Largely dealing with political topics, the memoir barely mentions her mother, husband or children.[196] Despite some degree of friction between Stanton and Anthony in their later years, on the dedication page Stanton said, "I dedicate this volume to Susan B. Anthony, my steadfast friend for half a century."[197]

Stanton continued to write articles prolifically for a variety of publications right up until she died.[198]

Death and burial

[edit]

Stanton died in New York City on October 26, 1902, 18 years before women achieved the right to vote in the United States via the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The medical report said the cause of death was heart failure. According to her daughter Harriet, she had developed breathing problems that had begun to interfere with her work. The day before she died, Stanton told her doctor, a woman, to give her something to speed her death if the problem could not be cured.[199] Stanton had signed a document two years earlier directing that her brain was to be donated to Cornell University for scientific study after her death, but her wishes in that regard were not carried out.[200] She was interred beside her husband in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.[201]

After Stanton's death, Susan B. Anthony wrote to a friend: "Oh, this awful hush! It seems impossible that voice is stilled which I have loved to hear for fifty years. Always I have felt I must have Mrs. Stanton's opinion of things before I knew where I stood myself. I am all at sea."[202]

Even after her death, foes of women's suffrage continued to use Stanton's more unorthodox statements to promote opposition to ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, which became law in 1920. Younger women in the suffrage movement responded by belittling Stanton and glorifying Anthony. In 1923, Alice Paul, leader of the National Women's Party, introduced the proposed Equal Rights Amendment in Seneca Falls on the 75th anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention. The planned ceremony and printed program made no mention of Stanton, the primary force behind the convention. One of the speakers was Stanton's daughter, Harriot Stanton Blatch, who insisted on paying tribute to her mother's role.[203] Aside from a collection of her letters published by her children, no significant book about Stanton was written until a full-length biography was published in 1940 with the assistance of her daughter. Stanton began to regain recognition for her role in the women's rights movement with the rise of the new feminist movement in the 1960s and the establishment of academic women's history programs.[204][205]

Commemorations

[edit]

Stanton is commemorated, along with Lucretia Mott and Susan B. Anthony, in the 1921 sculpture Portrait Monument by Adelaide Johnson in the United States Capitol. Placed for years in the crypt of the capitol building, it was moved in 1997 to a more prominent location in the U.S. Capitol rotunda.[206]

In 1965, the Elizabeth Cady Stanton House in Seneca Falls was declared a National Historic Landmark. It is now part of the Women's Rights National Historical Park.[207]

In 1969, the group New York Radical Feminists was founded. It was organized into small cells or "brigades" named after notable feminists of the past; Anne Koedt and Shulamith Firestone led the Stanton-Anthony Brigade.[208]

In 1973, Stanton was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[209]

In 1975, the Elizabeth Cady Stanton House in Tenafly, New Jersey, was declared a National Historic Landmark.[210]

In 1982, the Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Papers project began work as an academic undertaking to collect and document all available materials written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. The six-volume "The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony" was published from the 14,000 documents collected by the project. The project has since ended.[211][212]

In 1999, Ken Burns and Paul Barnes produced the documentary Not for Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony,[213] which won a Peabody Award.[214]

In 1999, a sculpture by Ted Aub was unveiled to commemorate the introduction of Stanton to Susan B. Anthony by Amelia Bloomer on May 12, 1851. This sculpture, called "When Anthony Met Stanton," consists of the three women depicted as life-size bronze statues. It overlooks Van Cleef Lake in Seneca Falls, New York, where the introduction occurred.[215][216]

The Elizabeth Cady Stanton Pregnant and Parenting Student Services Act was introduced into Congress in 2005 to fund services for students who were pregnant or already were parents. It did not become law.[217]

In 2008, 37 Park Row, the site of the office of Stanton and Anthony's newspaper, The Revolution, was included in the map of Manhattan historical sites related to women's history that was created by the Office of the Manhattan Borough President.[218]

Stanton is commemorated, together with Amelia Bloomer, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Ross Tubman, in the calendar of saints of the Episcopal Church on July 20 of each year.[219]

The U.S. Treasury Department announced in 2016 that an image of Stanton would appear on the back of a newly designed $10 bill along with Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Alice Paul and the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession. New $5, $10 and $20 bills were planned to be introduced in 2020 in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of American women winning the right to vote, but were delayed.[220][221]

In 2020, the Women's Rights Pioneers Monument was unveiled in Central Park in New York City on the 100th anniversary of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment giving women the right to vote. Created by Meredith Bergmann, this sculpture depicts Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Sojourner Truth engaged in animated discussion.[222]

See also

[edit]- History of feminism

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's rights activists

- Statue of Elizabeth Cady Stanton

- Timeline of women's suffrage

Notes

[edit]- ^ DuBois Feminism & Suffrage, p. 41

- ^ Davis, Angela (1983). Women, Race & Class (First ed.). New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 288. ISBN 978-0394713519. OCLC 760446965.

- ^ Griffith, pp. 3–5

- ^ Ginzberg, p. 19

- ^ Griffith, pp. 5–7

- ^ Stanton, Eighty Years & More, pp. 5, 14–17

- ^ Ginzberg, pp. 20–21

- ^ Stanton, Eighty Years & More, pp. 33, 48

- ^ a b c Griffith, pp. 6–9, 16–17

- ^ Stanton, Eighty Years & More, p. 20

- ^ Stanton, Eighty Years & More, p. 43

- ^ Ginzberg, pp. 24–25

- ^ Griffith, p. 24

- ^ Dann, Norman K. (2016). Ballots, Bloomers and Marmalade. The Life of Elizabeth Smith Miller. Hamilton, New York: Log Cabin Books. p. 67. ISBN 9780997325102.

- ^ Stanton, Eighty Years & More, p. 72

- ^ McMIllen, p. 96

- ^ Stanton, Eighty Years & More, p. 127

- ^ Baker, p.110–111

- ^ Griffith, p. 66

- ^ Baker, pp. 106–108

- ^ Quoted in Baker, p. 109

- ^ Baker, pp. 109–113

- ^ Baker, p.113

- ^ Stanton, Eighty Years & More, pp. 146–148

- ^ Griffith, p. 80

- ^ Baker, p. 102

- ^ Baker, p.115

- ^ Ginzberg, p. 87

- ^ McMillen, pp. 72–75

- ^ Griffith, p. 37

- ^ Ginzberg, p. 41

- ^ a b Stanton, Eighty Years and More, p. 148

- ^ McMillen, p. 86

- ^ Dubois, The Elizabeth Cady Stanton – Susan B. Anthony Reader, pp. 12–13

- ^ Wellman, pp. 193–195

- ^ Women's Rights National Historical Park, National Park Service, "All Men and Women Are Created Equal"

- ^ McMillen, pp. 90–01. Griffith says on p. 41 that Stanton had earlier spoken to a smaller group of women on temperance and women's rights.

- ^ Quoted in Ginzberg, p. 59

- ^ Wellman, p. 203

- ^ Griffith, p. 6

- ^ McMillen, pp. 99–100

- ^ Wellman, p. 192

- ^ Mari Jo and Paul Buhle, The Concise History of Woman Suffrage, 1978, p. 90

- ^ McMillen 95–96

- ^ a b c d e f g h Katz, Elizabeth D. (July 30, 2021). "Sex, Suffrage, and State Constitutional Law: Women's Legal Right to Hold Public Office". Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. Rochester, NY. SSRN 3896499.

- ^ Griffith, p. 65. Stanton's sister Catherine Wilkeson signed the Call to the 1850 convention, according to Ginzberg, p. 220, footnote 55.

- ^ Ginzberg, p. 77

- ^ Quoted in McMillen, pp. 109–110

- ^ Barry, p. 297

- ^ Barry, p. 63

- ^ a b c Griffith, p. 74

- ^ Barry, p. 64

- ^ Stanton, Eighty Years and More, p. 165.

- ^ Gordon, Vol 1, p. xxx

- ^ Griffith, pp. 108, 224

- ^ Harper, Vol 1, p. 396

- ^ McMillen, pp. 52–53

- ^ Flexner, p. 58

- ^ Susan B. Anthony, "Fifty Years of Work for Woman" Independent, 52 (February 15, 1900), pp. 414–417, as quoted in Sherr, Lynn, Failure Is Impossible: Susan B. Anthony in Her Own Words, Random House, New York, 1995, p. 134

- ^ Harper, Vol. 1, pp. 64–68.

- ^ Griffith, p. 76

- ^ Harper, Vol. 1, p. 67

- ^ Harper, Vol. 1, p. 68

- ^ Harper, Vol. 1, pp. 92–95

- ^ Griffith, p. 77

- ^ DuBois, The Elizabeth Cady Stanton – Susan B. Anthony Reader, p. 15

- ^ Griffith, p. 87

- ^ a b Ginzberg, p. 17

- ^ Quoted in Wellman, p. 136

- ^ McMillen, p. 19

- ^ Nancy Cott, Public Vows: A History of Marriage and the Nation (2000). Cott says that "state legislatures’ flurry of activity in passing laws on divorce and married women’s property showed their hand: marriage was their political creation" p 54; and "the doctrine of coverture was being unseated in social thought and substantially defeated in the law." p. 157.

- ^ Wellman, pp. 145–146

- ^ Griffith, p. 43

- ^ McMillen, p. 81

- ^ a b Griffith, pp. 100–101

- ^ Harper, Vol. 1, pp. 104, 122–28

- ^ Griffith, pp. 82–83

- ^ Address to Judiciary Committee of the New York State Legislature, from the web site of the Catt Center at Iowa State University

- ^ Griffith, pp. 64, 71, 79

- ^ a b Griffith, pp. 101–104

- ^ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, History of Woman Suffrage Vol 1, p. 719

- ^ Barry, p. 137

- ^ Ginzberg, p. 148

- ^ Quoted in DuBois, Woman Suffrage and Women's Rights, p. 169

- ^ a b Venet, p. 27. Confusingly, the Catt Center at Iowa State University reprints under the title A Slaves Appeal Stanton's speech to the New York Assembly in that same year, in which she compares the situation of women in some ways to slavery.

- ^ a b Elizabeth Cady Stanton, The Slaves Appeal, 1860, Weed, Parsons and Company, Printers; Albany, New York

- ^ Venet, pp. 26–29, 32

- ^ Griffith, p. 106

- ^ a b Ginzberg, pp. 108–110

- ^ Judith E. Harper. "Biography". Not for Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Public Broadcasting System. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ Venet, p. 148. The League was called by several variations of its name, including the Women's National Loyal League.

- ^ Barry, p. 154

- ^ Harper (1899), p. 238

- ^ Venet, p. 105

- ^ Venet, pp. 105, 116

- ^ Flexner, p. 105

- ^ Venet, pp. 1, 122

- ^ Letter from Stanton to Gerrit Smith, January 1, 1866, quoted in DuBois, Feminism & Suffrage, p. 61

- ^ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, Vol II, pp. 91, 97

- ^ A Petition For Universal Suffrage Archived May 25, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, at the U.S. National Archives

- ^ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, Vol II, pp. 152–53

- ^ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, Vol II, pp. 171–172

- ^ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, Vol II, p. 174

- ^ Griffith, p. 125

- ^ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, Vol II, p. 270

- ^ Dudden, p. 76

- ^ Ginzberg, pp. 120–121

- ^ Dudden, p. 105

- ^ DuBois, Feminism & Suffrage, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Dudden, pp. 137 and 246, footnotes 22 and 25

- ^ Baker, p. 126

- ^ Rakow and Kramarae, pp. 47–51

- ^ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 2, p. 384. Stone is speaking here during the final AERA convention in 1869.

- ^ DuBois Feminism & Suffrage, pp. 175–178

- ^ Rakow and Kramarae, p. 48

- ^ Elizabeth Cady Stanton, "The Sixteenth Amendment," The Revolution, April 29, 1869, p. 266. Quoted in DuBois Feminism & Suffrage, p. 178.

- ^ Elizabeth Cady Stanton, "Manhood Suffrage," The Revolution, December 24, 1868. Reproduced in Gordon, Vol 5, p. 196

- ^ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 2, pp. 382–383

- ^ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, p. 382

- ^ Philip S. Foner, editor. Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings. Lawrence Hill Books, Chicago, 1999, p. 600

- ^ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, p. 193