Cirth

| Cirth | |

|---|---|

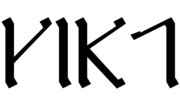

The word "Cirth" written using the Cirth in the Angerthas Daeron mode | |

| Script type | |

| Creator | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Direction | Varies |

| Languages | Khuzdul, Sindarin, Quenya, Westron, English |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Cirt (291), Cirth |

The Cirth (Sindarin pronunciation: [ˈkirθ], meaning "runes"; sg. certh [ˈkɛrθ]) is a semi‑artificial script, based on real‑life runic alphabets, one of several scripts invented by J. R. R. Tolkien for the constructed languages he devised and used in his works. Cirth is written with a capital letter when referring to the writing system; the letters themselves can be called cirth.

In the fictional history of Middle-earth, the original Certhas was created by the Sindar (or Grey Elves) for their language, Sindarin. Its extension and elaboration was known as the Angerthas Daeron, as it was attributed to the Sinda Daeron, despite the fact that it was most probably arranged by the Noldor in order to represent the sounds of other languages like Quenya and Telerin.

Although it was later largely replaced by the Tengwar, the Cirth was nonetheless adopted by the Dwarves to write down both their Khuzdul language (Angerthas Moria) and the languages of Men (Angerthas Erebor). The Cirth was also adapted, in its oldest and simplest form, by various races including Men and even Orcs.

External history

[edit]Concept and creation

[edit]

Many letters have shapes also found in the historical runic alphabets, but their sound values are only similar in a few of the vowels. Rather, the system of assignment of sound values is much more systematic in the Cirth than in the historical runes (e.g., voiced variants of a voiceless sound are expressed by an additional stroke).

The division between the older Cirth of Daeron and their adaptation by Dwarves and Men has been interpreted as a parallel drawn by Tolkien to the development of the Fuþorc to the Younger Fuþark.[1] The original Elvish Cirth "as supposed products of a superior culture" are focused on logical arrangement and a close connection between form and value whereas the adaptations by mortal races introduced irregularities. Similar to the Germanic tribes who had no written literature and used only simple runes before their conversion to Christianity, the Sindarin Elves of Beleriand with their Cirth were introduced to the more elaborate Tengwar of Fëanor when the Noldorin Elves returned to Middle-earth from the lands of the divine Valar.[2]

Internal history and description

[edit]Certhas

[edit]In the Appendix E to The Return of the King, Tolkien writes that the Sindar of Beleriand first developed an alphabet for their language some time between the invention of the Tengwar by Fëanor (YT 1250) and the introduction thereof to Middle-earth by the Exiled Noldor at the beginning of the First Age.[3]

This alphabet was devised to represent only the sounds of their Sindarin language and its letters were mostly used for inscribing names or brief memorials on wood, stone or metal, hence their angular shapes and straight lines.[3] In Sindarin these letters were named cirth (sing. certh), from the Elvish root *kir- meaning "to cleave, to cut".[4] An abecedarium of cirth, consisting of the runes listed in due order, was commonly known as Certhas ([ˈkɛrθɑs], meaning "rune-rows" in Sindarin and loosely translated as "runic alphabet"[5]).

The oldest cirth were the following:[3]

| Consonants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vowels |

The form of these letters was somewhat unsystematic, unlike later rearrangements and extensions that made them more featural.[3] The cirth ![]() and

and ![]() were used for ⟨h⟩ and ⟨s⟩, but varied as to which was which.[3] Many of the runes consisted of a single vertical line (or "stem") with an appendage (or "branch") attached to one or both sides. If the attachment was made on one side only, it was usually to the right, but "the reverse was not infrequent" and did not change the value of the letter.[3] (For example, the variants

were used for ⟨h⟩ and ⟨s⟩, but varied as to which was which.[3] Many of the runes consisted of a single vertical line (or "stem") with an appendage (or "branch") attached to one or both sides. If the attachment was made on one side only, it was usually to the right, but "the reverse was not infrequent" and did not change the value of the letter.[3] (For example, the variants ![]() or

or ![]() specifically mentioned for h or s, also

specifically mentioned for h or s, also ![]() or

or ![]() for t, etc.).

for t, etc.).

Angerthas Daeron

[edit]In Beleriand, before the end of the First Age, the Certhas was rearranged and further developed, partly under the influence of the Tengwar introduced by the Noldor. This reorganisation of the Cirth was commonly attributed to the Elf Daeron, minstrel and loremaster of King Thingol of Doriath. Thus, the new system became known as the Angerthas Daeron[3] (where "angerthas" [ɑŋˈɡɛrθɑs] is from Sindarin "an(d)" [ɑn(d)] + "certhas" [ˈkɛrθɑs], meaning "long rune-rows"[6]).

In this arrangement, the assignment of values to each certh is systematic. The runes consisting of a stem and a branch attached to the right are used for voiceless stops, while other sounds are allocated according to the following principles:[3]

- adding a stroke to a branch adds voice (e.g.,

[p] →

[p] →  [b]);

[b]); - moving the branch to the left indicates opening to a spirant (e.g.,

[t] →

[t] →  [θ]);

[θ]); - placing the branch on both sides of the stem adds voice and nasality (e.g.,

[k] →

[k] →  [ŋ]).

[ŋ]).

The cirth constructed in this way can therefore be arranged into series, each corresponding to a place of articulation:

- labial consonants, based on

;

; - dental consonants, based on

;

; - front consonants, based on

;

; - velar consonants, based on

;

; - labialized velar consonants, based on

.

.

Other letters introduced in this system include: ![]() and

and ![]() for ⟨a⟩ and ⟨w⟩, respectively; runes for long vowels, evidently originated by doubling and binding the certh of the corresponding short vowel (e.g.,

for ⟨a⟩ and ⟨w⟩, respectively; runes for long vowels, evidently originated by doubling and binding the certh of the corresponding short vowel (e.g., ![]()

![]() ⟨oo⟩ →

⟨oo⟩ → ![]() ⟨ō⟩); two front vowels, probably stemming from ligatures of the corresponding back vowel with the ⟨i⟩-certh (i.e.,

⟨ō⟩); two front vowels, probably stemming from ligatures of the corresponding back vowel with the ⟨i⟩-certh (i.e., ![]()

![]() →

→ ![]() ⟨ü⟩, and

⟨ü⟩, and ![]()

![]() →

→ ![]() ⟨ö⟩); some homorganic nasal + stop clusters (e.g.,

⟨ö⟩); some homorganic nasal + stop clusters (e.g., ![]() [nd]).

[nd]).

Back to the fictional history, since the new ![]() -series and

-series and ![]() -series encompass sounds which do not occur in Sindarin but are present in Quenya, they were most probably introduced by the Exiled Noldor[3] who spoke Quenya as a language of knowledge.

-series encompass sounds which do not occur in Sindarin but are present in Quenya, they were most probably introduced by the Exiled Noldor[3] who spoke Quenya as a language of knowledge.

By loan-translation, the Cirth became known in Quenya as Certar [ˈkɛrtar], while a single certh was called certa [ˈkɛrta].

After the Tengwar became the sole script used for writing, the Angerthas Daeron was essentially relegated to carved inscriptions. The Elves of the West, for the most part, abandoned the Cirth altogether, with the exception of the Noldor dwelling in the country of Eregion, who maintained it in use[3] and made it known as Angerthas Eregion.

Note: In this article, the runes of the Angerthas come with the same peculiar transliteration used by Tolkien in the Appendix E, which differs from the (Latin) spelling of both Quenya and Sindarin. The IPA transcription that follows is applicable to both languages, except where indicated otherwise.

| Labial consonants |

Certh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | p | b | f | v | m[i] | mh, mb | ||

| IPA | [p] | [b] | [f] | [v] | [m] | (S.) [ṽ] (Q.) [mb] | ||

| Dental consonants |

Certh | |||||||

| Transliteration | t | d | th | dh | n | nd[ii] | ||

| IPA | [t] | [d] | [θ] | [ð] | [n] | [nd] | ||

| Front consonants[iii] |

Certh | |||||||

| Transliteration | ch[iv] | j[v] | sh[vi] | zh | nj[vii] | |||

| IPA | (N.) | [c⁽ȷ̊⁾] | [ɟj] | [ç] | [ʝ] | ɟ[ɲj] ← [ɲɟj] | ||

| (V.) | [t͡ʃ] | [d͡ʒ] | [ʃ] | [ʒ] | [nd͡ʒ] | |||

| Velar consonants |

Certh | |||||||

| Transliteration | k | g | kh | gh | ŋ | ng | ||

| IPA | [k] | [ɡ] | [x] | [ɣ] | [ŋ] | [ŋɡ] | ||

| Labiovelar consonants |

Certh | |||||||

| Transliteration | kw[7] | gw[8] | khw | ghw | nw[viii] | ngw[8] | ||

| IPA | (Q.) | [kʷ₍w̥₎] | [ɡʷw] | [ʍ] | [w] | [nʷw]←[ŋʷw] | [ŋɡʷw] | |

| Consonants | Certh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | r | rh | l | lh | s | ss or z[ix] | h[x] | |

| IPA | [r] | [r̥] | [l] | [l̥] | [s] | [sː] or [z] | [h] | |

| Approximants | Certh | |||||||

| Transliteration | w | hw[xi] | ||||||

| IPA | [w] | [ʍ] | ||||||

| Vowels | Certh | |||||||

| Transliteration | i, y | u | e | a | o | |||

| IPA | [i], [j] | [u] | [e] | [a] | [o] | |||

| Long vowels |

Certh | |||||||

| Transliteration | ū | ē | ā | ō | ||||

| IPA | [uː] | [eː] | [aː] | [oː] | ||||

| Fronted vowels |

Certh | |||||||

| Transliteration | ü | ö | ||||||

| IPA | [y] | [œ] | ||||||

Notes:

- ^ According to the principles outlined above, the labial nasal would be assigned to the certh

. However, archaic Sindarin had two labial nasals: the occlusive [m], and the spirant [ṽ][9] (spelt ⟨mh⟩). Since the ⟨mh⟩ sound could best be represented by a reversal of the sign for ⟨m⟩ (to indicate its spirantization), the reversible

. However, archaic Sindarin had two labial nasals: the occlusive [m], and the spirant [ṽ][9] (spelt ⟨mh⟩). Since the ⟨mh⟩ sound could best be represented by a reversal of the sign for ⟨m⟩ (to indicate its spirantization), the reversible  was given the value ⟨m⟩, and

was given the value ⟨m⟩, and  was assigned to ⟨mh⟩.[3] The sound [ṽ] merged with [v] in later Sindarin.

was assigned to ⟨mh⟩.[3] The sound [ṽ] merged with [v] in later Sindarin. - ^ The certh

was not clearly related in shape to the dentals.[3]

was not clearly related in shape to the dentals.[3] - ^ The

-series, which represents the front consonants of Quenya, is essentially the Cirth counterpart to the Tengwar tyelpetéma (column III in the General Use).

-series, which represents the front consonants of Quenya, is essentially the Cirth counterpart to the Tengwar tyelpetéma (column III in the General Use).

In this article, each certh of this series comes with two IPA transcriptions. The reason is that these consonants are realised as palatals in Noldorin Quenya, but as postalveolars in Vanyarin Quenya. Although the Angerthas Daeron was devised for the Noldorin variety, it is deemed necessary to show the Vanyarin pronunciation as well, given that the very transliteration used by Tolkien is more akin to the Vanyarin phonology. - ^ The certh

indicates Quenya ⟨ty⟩, which is pronounced [c⁽ȷ̊⁾] in Noldorin[10] but is a voiceless postalveolar affricate [t͡ʃ] in Vanyarin.[11]

indicates Quenya ⟨ty⟩, which is pronounced [c⁽ȷ̊⁾] in Noldorin[10] but is a voiceless postalveolar affricate [t͡ʃ] in Vanyarin.[11] - ^ The certh

represents Quenya ⟨dy⟩, formerly pronounced [ɟj].[12]

represents Quenya ⟨dy⟩, formerly pronounced [ɟj].[12] - ^ The certh

stands for Quenya ⟨hy⟩, which is a voiceless palatal fricative [ç] in Noldorin[13] and a voiceless postalveolar fricative [ʃ] in Vanyarin.[11]

stands for Quenya ⟨hy⟩, which is a voiceless palatal fricative [ç] in Noldorin[13] and a voiceless postalveolar fricative [ʃ] in Vanyarin.[11] - ^ The certh

denotes Quenya ⟨ndy⟩, formerly pronounced [ɲɟj]. In Noldorin, this cluster was later reduced to ⟨ny⟩[14] (articulated as [ɲj][15]). On the other hand, in Vanyarin, the cluster underwent assibilation, turning into [nd͡ʒ].[11]

denotes Quenya ⟨ndy⟩, formerly pronounced [ɲɟj]. In Noldorin, this cluster was later reduced to ⟨ny⟩[14] (articulated as [ɲj][15]). On the other hand, in Vanyarin, the cluster underwent assibilation, turning into [nd͡ʒ].[11] - ^ The certh

, much like the tengwa

, much like the tengwa  "ñwalme", formerly represented Quenya ⟨ñw⟩ (pronounced [ŋʷw]), occurring only in initial position. This sound later evolved into [nʷw], explaining the transliteration of this certh as ⟨nw⟩. Non-initial occurrences of [nʷw] are most probably interpreted as ⟨n⟩+⟨w⟩ (i.e., two separate cirth).[16]

"ñwalme", formerly represented Quenya ⟨ñw⟩ (pronounced [ŋʷw]), occurring only in initial position. This sound later evolved into [nʷw], explaining the transliteration of this certh as ⟨nw⟩. Non-initial occurrences of [nʷw] are most probably interpreted as ⟨n⟩+⟨w⟩ (i.e., two separate cirth).[16] - ^ The certh

, the theoretical value of which is ⟨z⟩, is instead used as ⟨ss⟩ in both Quenya and Sindarin (cf. the tengwa

, the theoretical value of which is ⟨z⟩, is instead used as ⟨ss⟩ in both Quenya and Sindarin (cf. the tengwa  "esse"/"áze").[3]

"esse"/"áze").[3] - ^ The new certh

was introduced for ⟨h⟩: it is similar in shape both to the certh

was introduced for ⟨h⟩: it is similar in shape both to the certh  (formerly used for ⟨h⟩, then reassigned to ⟨ty⟩) and to the tengwa

(formerly used for ⟨h⟩, then reassigned to ⟨ty⟩) and to the tengwa  "hyarmen".

"hyarmen". - ^ The certh

, the theoretical value of which was ⟨m⟩, was used for Sindarin ⟨hw⟩ for the reasons stated above[3] (cf. the tengwa

, the theoretical value of which was ⟨m⟩, was used for Sindarin ⟨hw⟩ for the reasons stated above[3] (cf. the tengwa  "hwesta sindarinwa").

"hwesta sindarinwa").

Angerthas Moria

[edit]According to Tolkien's legendarium, the Dwarves first came to know the runes of the Noldor at the beginning of the Second Age. The Dwarves "introduced a number of unsystematic changes in value, as well as certain new cirth".[3] They modified the previous system to suit the specific needs of their language, Khuzdul. The Dwarves spread their revised alphabet to Moria, where it came to be known as Angerthas Moria, and developed both carved and pen-written forms of these runes.[3]

Many cirth here represent sounds not occurring in Khuzdul[17] (at least in published words of Khuzdul: of course, our corpus is very limited to judge the necessity or not, of these sounds). Here they are marked with a black star (★).

| Certh | Translit. | IPA' | Certh | Translit. | IPA | Certh | Translit. | IPA' | Certh | Translit. | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | /p/★ | l | /l/ | e | /e/ | ||||||

| b | /b/ | z | /z/ | lh | /ɬ/★ | ê | /eː/ | ||||

| f | /f/ | k | /k/ | nd | /nd/ | a | /a/ | ||||

| v | /v/★ | g | /ɡ/ | h[A] | /h/ | â | /aː/ | ||||

| hw | /ʍ/★ | kh | /x/★ | ʻ [A] | /ʔ/ | o | /o/ | ||||

| m | /m/ | gh | /ɣ/★ | ŋ | /ŋ/★ | ô | /oː/ | ||||

| mb | /mb/ | n | /n/ | ng | /ŋɡ/ | ö | /œ/★ | ||||

| t | /t/ | kw | /kʷ/★ | nj | /ndʒ/★ | n | /n/ | ||||

| d | /d/ | gw | /ɡʷ/★ | i | /i/ | s | /s/ | ||||

| th | /θ/★ | khw | /xʷ/★ | y | /j/ | [B] | /ə/ | ||||

| dh | /ð/★ | ghw | /ɣʷ/★ | hy | /j̊, ç/★ | [B] | /ʌ/ | ||||

| r | /ʀ, ʁ, r/ | ngw | /ŋɡʷ/★ | u | /u/ | ||||||

| ch | /tʃ, c/★ | nw | /nʷ/★ | û | /uː/ | ||||||

| j | /dʒ, ɟ/★ | w | /w/★ | +h[C] | /◌ʰ/ | ||||||

| sh | /ʃ/ | zh | /ʒ/★ | ü | /y/★ | &[D] | |||||

Notes:

| A. | ^ The Khuzdul language has two glottal consonants: /h/ and /ʔ/, the latter being "the glottal beginning of a word with an initial vowel".[3] Thus, in need of a reversible certh to represent these sounds, |

| B. | ^ These cirth were a halved form of |

| C. | ^ This letter denotes aspiration in voiceless stops, occurring frequently in Khuzdul as kh and th.[3] |

| D. | ^ This certh is a scribal abbreviation used to represent a conjunction, and is basically identical to the ampersand ⟨&⟩ used in Latin script. |

In Angerthas Moria the cirth ![]() /dʒ/ and

/dʒ/ and ![]() /ʒ/ were dropped. Thus

/ʒ/ were dropped. Thus ![]() and

and ![]() were adopted for /dʒ/ and /ʒ/, although they were used for /r/ and /r̥/ in Elvish languages. Subsequently, this script used the certh

were adopted for /dʒ/ and /ʒ/, although they were used for /r/ and /r̥/ in Elvish languages. Subsequently, this script used the certh ![]() for /ʀ/ (or /ʁ/), which had the sound /n/ in the Elvish systems. Therefore, the certh

for /ʀ/ (or /ʁ/), which had the sound /n/ in the Elvish systems. Therefore, the certh ![]() (which was previously used for the sound /ŋ/, useless in Khuzdul) was adopted for the sound /n/. A totally new introduction was the certh

(which was previously used for the sound /ŋ/, useless in Khuzdul) was adopted for the sound /n/. A totally new introduction was the certh ![]() , used as an alternative, simplified and, maybe, weaker form of

, used as an alternative, simplified and, maybe, weaker form of ![]() . Because of the visual relation of these two cirth, the certh

. Because of the visual relation of these two cirth, the certh ![]() was given the sound /z/ to relate better with

was given the sound /z/ to relate better with ![]() that, in this script, had the sound /s/.[3]

that, in this script, had the sound /s/.[3]

Angerthas Erebor

[edit]At the beginning of the Third Age the Dwarves were driven out of Moria, and some migrated to Erebor. As the Dwarves of Erebor would trade with the Men of the nearby towns of Dale and Lake-town, they needed a script to write in Westron (the lingua franca of Middle-earth, usually rendered in English by Tolkien in his works). The Angerthas Moria was adapted accordingly: some new cirth were added, while some were restored to their Elvish usage, thus creating the Angerthas Erebor.[3]

While the Angerthas Moria was still used to write down Khuzdul, this new script was primarily used for Mannish languages. It is also the script used in the first and third page of the Book of Mazarbul.[citation needed]

| Certh | Translit. | IPA | Certh | Translit. | IPA | Certh | Translit. | IPA | Certh | Translit. | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | /p/ | zh | /ʒ/ | l | /l/ | e | /e/ | ||||

| b | /b/ | ks | /ks/ | ||||||||

| f | /f/ | k | /k/ | nd | /nd/ | a | /a/ | ||||

| v | /v/ | g | /ɡ/ | s | /s/ | ||||||

| hw | /ʍ/ | kh | /x/ | o | /o/ | ||||||

| m | /m/ | gh | /ɣ/ | ŋ | /ŋ/ | ||||||

| mb | /mb/ | n | /n/ | ng | /ŋɡ/ | ö | /œ/ | ||||

| t | /t/ | kw | /kʷ/ | n | /n/ | ||||||

| d | /d/ | gw | /ɡʷ/ | i | /i/ | h | /h/ | ||||

| th | /θ/ | khw | /xʷ/ | y | /j/ | /ə/ | |||||

| dh | /ð/ | ghw | /ɣʷ/ | hy | /j̊/ or /ç/ | /ʌ/ | |||||

| r | /r/ | ngw | /ŋɡʷ/ | u | /u/ | ps | /ps/ | ||||

| ch | /tʃ/ | nw | /nʷ/ | z | /z/ | ts | /ts/ | ||||

| j | /dʒ/ | g | /ɡ/ | w | /w/ | +h | /◌ʰ/ | ||||

| sh | /ʃ/ | gh | /ɣ/ | ü | /y/ | & | |||||

Angerthas Erebor also features combining diacritics:

- a circumflex

used to denote long consonants;

used to denote long consonants; - a macron below

to indicate a long vowel sound;

to indicate a long vowel sound; - an underdot

to mark cirth used as numerals. As a matter of fact, in the Book of Mazarbul some cirth are used as numerals:

to mark cirth used as numerals. As a matter of fact, in the Book of Mazarbul some cirth are used as numerals:  for 1,

for 1,  for 2,

for 2,  for 3,

for 3,  for 4,

for 4,  for 5.

for 5.

The Angerthas Erebor is used twice in The Lord of the Rings to write in English:

- in the upper inscription of the title page, where it reads "[dh]ə·lord·ov·[dh]ə·riŋs·translatᵊd·from·[dh]ə·red·b[oo]k' ..." (the sentence follows in the bottom inscription, written in Tengwar: "... of Westmarch by John Ronald Reuel Tolkien. Herein is set forth/ the history of the War of the Ring and the Return of the King as seen by the Hobbits.");

- in the bottom inscription of Balin's tomb—being the translation of the upper inscription, which is written in Khuzdul using Angerthas Moria.

The Book of Mazarbul shows some additional cirth used in Angerthas Erebor: one for a double ⟨l⟩ ligature, one for the definite article, and six for the representation of the same number of English diphthongs:

| Certh | English spelling |

|---|---|

| ⟨ll⟩ | |

| ⟨the⟩[A] | |

| ⟨ai⟩, ⟨ay⟩ | |

| ⟨au⟩, ⟨aw⟩ | |

| ⟨ea⟩ | |

| ⟨ee⟩ | |

| ⟨eu⟩, ⟨ew⟩ | |

| ⟨oa⟩ | |

| ⟨oo⟩ | |

| ⟨ou⟩, ⟨ow⟩ |

Notes:

| A. | ^ This certh is a scribal abbreviation used to represent the definite article. Although in English it stands for ⟨the⟩, it can assume different values according to the used language. |

| ∗. | ^ The cirth marked with an asterisk are unique to Angerthas Erebor. |

Other runic scripts by Tolkien

[edit]The Cirth is not the only runic writing system used by Tolkien in his legendarium. In fact, he devised a great number of runic alphabets, of which only a few others have been published. Some of these are included in the "Appendix on Runes" of The Treason of Isengard (The History of Middle-earth, vol. VII), edited by Christopher Tolkien.[18]

Runes from The Hobbit

[edit]According to Tolkien himself, those found in The Hobbit are a form of "English runes" used in lieu of the Dwarvish runes proper.[19] They can be interpreted as an attempt made by Tolkien to adapt the Fuþorc (i.e., the Old English runic alphabet) to the Modern English language.[20]

These runes are basically the same found in Fuþorc, but their sound may change according to their position, just like the letters of the Latin script: the writing mode used by Tolkien is, in this case, mainly orthographic.[21] This means that the system has one rune for each Latin letter, regardless of pronunciation.[21] For example, the rune ![]() ⟨c⟩ can sound /k/ in ⟨cover⟩, /s/ in ⟨sincere⟩, /ʃ/ in ⟨special⟩, and even /tʃ/ in the digraph

⟨c⟩ can sound /k/ in ⟨cover⟩, /s/ in ⟨sincere⟩, /ʃ/ in ⟨special⟩, and even /tʃ/ in the digraph ![]()

![]() ⟨ch⟩.[22]

⟨ch⟩.[22]

A few sounds are instead written with the same rune, without considering the English spelling. For example, the sound /ɔː/ is always written with the rune ![]() whether in English it is spelt ⟨o⟩ as in ⟨north⟩, ⟨a⟩ as in ⟨fall⟩, or ⟨oo⟩ as in ⟨door⟩. The only two letters that are subject to this phonemic spelling are ⟨a⟩ and ⟨o⟩.[21]

whether in English it is spelt ⟨o⟩ as in ⟨north⟩, ⟨a⟩ as in ⟨fall⟩, or ⟨oo⟩ as in ⟨door⟩. The only two letters that are subject to this phonemic spelling are ⟨a⟩ and ⟨o⟩.[21]

Finally, some runes stand for particular English digraphs and diphthongs.[19][21]

Here the runes used in The Hobbit are displayed along with their Fuþorc counterpart and corresponding English grapheme:

| Rune | Fuþorc | English grapheme | Rune | Fuþorc | English grapheme | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᚪ | phonemic[i] | ᚱ | ⟨r⟩ | |||

| ᚫ | ᛋ | ⟨s⟩ | ||||

| ᛒ | ⟨b⟩ | ᛏ | ⟨t⟩ | |||

| ᚳ | ⟨c⟩ | ᚢ | ⟨u⟩, ⟨v⟩ | |||

| ᛞ | ⟨d⟩ | ᚹ | ⟨w⟩ | |||

| ᛖ | ⟨e⟩ | ᛉ | ⟨x⟩ | |||

| ᚠ | ⟨f⟩, ⟨ph⟩ | ᚣ | ⟨y⟩ | |||

| ᚷ | ⟨g⟩ | ᛣ | ⟨z⟩[iii] | |||

| ᚻ | ⟨h⟩ | ᚦ | ⟨th⟩ | |||

| ᛁ | ⟨i⟩, ⟨j⟩ | ᛠ | ⟨ea⟩ | |||

| ᛱ [ii] | ⟨k⟩ | ᛥ | ⟨st⟩ | |||

| ᛚ | ⟨l⟩ | ᛟ | ⟨ee⟩ | |||

| ᛗ | ⟨m⟩ | ᛝ | ⟨ng⟩ | |||

| ᚾ | ⟨n⟩ | ᛇ | ⟨eo⟩ | |||

| ᚩ | phonemic[i] | ᛳ [ii] | ⟨oo⟩ | |||

| ᛈ | ⟨p⟩ | ᛲ [ii] | ⟨sh⟩ |

Notes:

| English grapheme | Sound value (IPA) |

Rune |

|---|---|---|

| ⟨a⟩ | /æ/ | |

| every other sound | ||

| /ɔː/ | ||

| ⟨o⟩ | every sound | |

| ⟨oo⟩ | /ɔː/ | |

| every other sound |

- ^ The three runes

,

,  , and

, and  were invented by Tolkien and are not attested in real-life Fuþorc.

were invented by Tolkien and are not attested in real-life Fuþorc. - ^ According to Tolkien, this is a "dwarf-rune" which "may be used if required" as an addendum to the English runes.[19]

- Tolkien commonly writes the English digraph ⟨wh⟩ (pronounced [ʍ] in some varieties of English) as

⟨hw⟩.

⟨hw⟩. - There is no rune to transliterate ⟨q⟩: the digraph ⟨qu⟩ (representing the sound [kʷw], like in ⟨queen⟩) is always written as

⟨cw⟩, reflecting the Anglo-Saxon spelling ⟨cƿ⟩.

⟨cw⟩, reflecting the Anglo-Saxon spelling ⟨cƿ⟩.

Gondolinic runes

[edit]Not all the runes mentioned in The Hobbit are Dwarf-runes. The swords found in the Trolls' cave bore runes that Gandalf could not read. In fact, the swords Glamdring and Orcrist (which were forged in the ancient kingdom of Gondolin) bore a type of letters known as Gondolinic runes. They seem to have become obsolete and been forgotten by the Third Age, and this is supported by the fact that only Elrond could still read the inscriptions on the swords.[19]

Tolkien devised this runic alphabet in a very early stage of his shaping of Middle-earth. Nevertheless, they are known to us from a slip of paper that Tolkien wrote; his son Christopher sent a photocopy of it to Paul Nolan Hyde in February 1992. Hyde published it, with an extensive analysis, in the 1992 Summer issue of Mythlore, no. 69.[23] The system was reanalyzed by Carl F. Hostetter, who corrected the reading of the χ̑ rune to a voiceless palatal fricative, aka the ich-laut.[24] Later, in Parma Eldalamberon 15, the original manuscript including a script variety of Gondolinic, the first cursive form of any of Tolkien's runic scripts, was presented.[25]

The system provides sounds not found in any of the known Elvish languages of the First Age, but perhaps it was designed for a variety of languages. However, the consonants seem to be, more or less, the same found in Welsh phonology, a theory supported by the fact that Tolkien was heavily influenced by Welsh when creating Elvish languages.[26]

| Labial | Dentals | Palatal | Dorsal | Glottal | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rune | IPA | Rune | IPA | Rune | IPA | Rune | IPA | Rune | IPA | Rune | IPA | Rune | IPA | ||||||||

| Plosive | p | /p/ | t | /t/ | k (c) | /k/ | |||||||||||||||

| b | /b/ | d | /d/ | g | /ɡ/ | ||||||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | /f/ | þ | /θ/ | s | /s/ | š | /ʃ/ | χ | /x/ | h | /h/ | |||||||||

| v | /v/ | ð | /ð/ | z | /z/ | ž | /ʒ/ | ||||||||||||||

| Affricate | tš (ch) | /t͡ʃ/ | |||||||||||||||||||

| dž (j) | /d͡ʒ/ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Nasal | m | /m/ | n | /n/ | ŋ | /ŋ/ | |||||||||||||||

| (mh) | /m̥/ | (ŋh) | /ŋ̊/ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Trill | r | /r/ | |||||||||||||||||||

| rh | /r̥/ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Lateral | l | /l/ | |||||||||||||||||||

| lh | /ɬ/ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Approximant | j (i̯) | /j/ | w (u̯) | /w/ | |||||||||||||||||

| χ̑ | /ç/? | ƕ | /ʍ/ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rune | IPA | Rune | IPA | Rune | IPA | Rune | IPA | Rune | IPA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | /a/ | e | /ɛ/ | i | /i/ | o | /ɔ/ | u | /u/ | |||||

| ā | /aː/ | ē | /eː/ | ī | /iː/ | ō | /oː/ | ū | /uː/ | |||||

| æ | /æ/ | œ | /œ/ | y | /y/ | |||||||||

| ǣ | /æː/ | œ̄ | /œː/ | ȳ | /yː/ | |||||||||

Encoding schemes

[edit]Unicode

[edit]Equivalents for some (but not all) cirth can be found in the Runic block of Unicode.

Tolkien's mode of writing Modern English in Anglo-Saxon runes received explicit recognition with the introduction of his three additional runes to the Runic block with the release of Unicode 7.0, in June 2014. The three characters represent the English ⟨k⟩, ⟨oo⟩ and ⟨sh⟩ graphemes, as follows:

- U+16F1 ᛱ RUNIC LETTER K

- U+16F2 ᛲ RUNIC LETTER SH

- U+16F3 ᛳ RUNIC LETTER OO

A formal Unicode proposal to encode Cirth as a separate script was made in September 1997 by Michael Everson.[27] No action was taken by the Unicode Technical Committee (UTC) but Cirth appears in the Roadmap to the SMP.[28]

ConScript Unicode Registry

[edit]| Cirth (in Private Use Area) | |

|---|---|

| Range | U+E080..U+E0FF (128 code points) |

| Plane | BMP |

| Scripts | Artificial Scripts |

| Major alphabets | Cirth |

| Assigned | 109 code points |

| Unused | 19 reserved code points |

| Source standards | CSUR |

| Note: Part of Private Use Area; possible conflicting fonts | |

Unicode Private Use Area layouts for Cirth are defined at the ConScript Unicode Registry (CSUR)[29] and the Under-ConScript Unicode Registry (UCSUR).[30]

Two different layouts are defined by the CSUR/UCSUR:

- 1997-11-03 proposal[31] implemented by fonts like GNU Unifont[32] and Code2000.

- 2000-04-22 discussion paper[33][34] implemented by fonts like Constructium and Fairfax.

Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols below instead of Cirth.

| Cirth (1997)[1][2] ConScript Unicode Registry 1997 code chart | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+E08x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+E09x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+E0Ax | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+E0Bx | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+E0Cx | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+E0Dx | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+E0Ex | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |||

| U+E0Fx | ||||||||||||||||

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

| Cirth (2000)[1][2] ConScript Unicode Registry 2000 proposal | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+E08x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+E09x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+E0Ax | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+E0Bx | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+E0Cx | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+E0Dx | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+E0Ex | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||

| U+E0Fx | ||||||||||||||||

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Simek, Rudolf (2005). Mittelerde: Tolkien und die germanische Mythologie [Middle-earth: Tolkien and Germanic Mythology] (in German). C. H. Beck. pp. 155–156. ISBN 3-406-52837-6.

- ^ Smith, Arden R. (1997). "The Semiotics of the Writing Systems of Tolkien's Middle-earth". In Rauch, Irmengard; Carr, Gerald F. (eds.). Semiotics Around the World: Synthesis in Diversity. Proceedings of the Fifth Congress of the International Association for Semiotic Studies, Berkeley, 1994. Vol. 1. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1239–1242. ISBN 978-3-11-012223-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. London: George Allen & Unwin. Appendix E.

- ^ "Sindarin Words: certh". eldamo.org. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ "Sindarin Words: certhas". eldamo.org. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ "Sindarin Words: angerthas". eldamo.org. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (2015-06-12). "The Feanorian Alphabet (Part 1) and Quenya Verb Structure: Qenya Grammar – Spelling and Transcription". Parma Eldalamberon (22): 66.

⟨q⟩ (⟨kw⟩) consists of a lip-rounded k̊ followed by a partly unvoiced w-offglide (more marked medially than initially).

- ^ a b Tolkien, J. R. R. (2015-06-12). "The Feanorian Alphabet (Part 1) and Quenya Verb Structure: Qenya Grammar – Spelling and Transcription". Parma Eldalamberon (22): 66.

⟨gw⟩ which only occurs in the medial group ⟨ngw⟩ is the voiced counterpart: a lip-rounded ɡ̊ followed by a w-offglide.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (2015-06-12). "The Feanorian Alphabet (Part 1) and Quenya Verb Structure: On Ælfwine's Spelling". Parma Eldalamberon (22): 67.

But he knew the old sign for 'nasal ṽ' and sometimes represents this (espec. where it is an initial variant on m) by ⟨mh⟩.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (2015-06-12). "The Feanorian Alphabet (Part 1) and Quenya Verb Structure: Qenya Grammar – Spelling and Transcription". Parma Eldalamberon (22): 66.

⟨ty⟩ is pronounced as a 'front explosive' [c], as e.g. Hungarian ty; but it is followed by an appreciable partly unvoiced y-offglide.

- ^ a b c "Quenya pronunciation". RealElvish.net. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (2015-06-12). "The Feanorian Alphabet (Part 1) and Quenya Verb Structure: Qenya Grammar – Spelling and Transcription". Parma Eldalamberon (22): 66.

⟨dy⟩ was formerly the voiced counterpart [ɟ] followed by a y-offglide.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (2015-06-12). "The Feanorian Alphabet (Part 1) and Quenya Verb Structure: Qenya Grammar – Spelling and Transcription". Parma Eldalamberon (22): 65.

⟨hy⟩ is an audibly spirant voiceless y, that is approximately [ç] as ch in German ich.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (2015-06-12). "The Feanorian Alphabet (Part 1) and Quenya Verb Structure: Qenya Grammar – Spelling and Transcription". Parma Eldalamberon (22): 66.

⟨dy⟩ ... only occurred in the group ⟨ndy⟩, which has become simplified to ⟨ny⟩.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (2015-06-12). "The Feanorian Alphabet (Part 1) and Quenya Verb Structure: Qenya Grammar – Spelling and Transcription". Parma Eldalamberon (22): 66.

n in ⟨ny⟩ is 'palatal n' but followed by (cf. ⟨ty⟩) a y-offglide, more marked medially (where ⟨ny⟩ counts as a group), less so initially).

- ^ "Amanye Tenceli: Tengwar - The Classical mode". Amanye Tenceli. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

ñwalme > nwalme. Only used for initial ⟨nw⟩, which developed from ⟨ñw⟩. Other occurrences of ⟨nw⟩ (originating in ⟨n⟩ + ⟨w⟩) are written númen + vilya.

- ^ Amram, Tess (2015). Aglab Khazad: The Secret Language of Tolkien's Dwarves (PDF) (BA). Swarthmore College.

- ^ Hyde, Paul Nolan (Summer 1990). "Quenti Lambardillion: Runing on Empty: Charting a New Course". Mythlore. 16 (4, no. 62).

- ^ a b c d Tolkien, J.R.R. (1937). The Hobbit. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- ^ Smith, Arden R. "Writing Systems". The Tolkien Estate. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

The runic alphabet used on Thror's Map and elsewhere in The Hobbit is not the Angerthas, but is rather the futhorc used by the Anglo-Saxons in England over a thousand years ago, adapted by Tolkien for the representation of modern English.

- ^ a b c d e Lindberg, Per (2016-11-27). "Tolkien English Runes" (PDF). forodrim.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-07-25. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- ^ Tolkien, J.R.R. (November 30, 1947). "Letter 112". Letter to Katherine Farrer. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ Hyde, Paul Nolan (July 1992). "Quenti Lambardillion: The 'Gondolinic Runes': Another Picture". Mythlore. 18 (3, no. 69).

- ^ Hostetter, Carl; Baynes, Pauline; Martsch, Nancy (1992-10-15). "Letters". Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature. 18 (4). ISSN 0146-9339.

- ^ J. R.R. Tolkien (author), Christopher Gilson et al (editor) (2004). Parma Eldalamberon 15.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Study explores JRR Tolkien's Welsh influences". BBC. 2011-05-21. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- ^ Everson, Michael (1997-09-18). "N1642: Proposal to encode Cirth in Plane 1 of ISO/IEC 10646-2". Working Group Document, ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

- ^ "Roadmap to the SMP". Unicode.org. 2015-06-03. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

- ^ "ConScript Unicode Registry". Evertype.com. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

- ^ "Under-ConScript Unicode Registry". Retrieved 2015-08-08.

- ^ "Cirth: U+E080–U+E0FF". ConScript Unicode Registry. 1997-11-03. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

- ^ "GNU Unifont". Unifoundry.com. Retrieved 2015-07-24.

- ^ Everson, Michael (2000-04-22). "X.X Cirth 1xx00–1xx7F" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2003-03-12. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

- ^ "Cirth, Range: E080–E0FF" (PDF). Under-ConScript Unicode Registry. 2008-04-14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-06-17. Retrieved 2015-08-08.