Genocides in history

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

|

| Issues |

| Related topics |

| Category |

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people[a] in whole or in part. The term was coined in 1944 by Raphael Lemkin. It is defined in Article 2 of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) of 1948 as "any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group, as such: killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group's conditions of life, calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; [and] forcibly transferring children of the group to another group."[1]

The preamble to the CPPCG states that "genocide is a crime under international law, contrary to the spirit and aims of the United Nations and condemned by the civilized world", and it also states that "at all periods of history genocide has inflicted great losses on humanity."[1] Genocide is widely considered to be the epitome of human evil,[2] and has been referred to as the "crime of crimes".[3][4][5] The Political Instability Task Force estimated that 43 genocides occurred between 1956 and 2016, resulting in 50 million deaths.[6] The UNHCR estimated that a further 50 million had been displaced by such episodes of violence.[6]

Definitions of genocide

[edit]The debate continues over what legally constitutes genocide. One definition is any conflict that the International Criminal Court has so designated. Mohammed Hassan Kakar argues that the definition should include political groups or any group so defined by the perpetrator.[7] He prefers the definition from Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn, which defines genocide as "a form of one-sided mass killing in which a state or other authority intends to destroy a group so defined by the perpetrator."[8]

In literature, some scholars have popularly emphasized the role that the Soviet Union played in excluding political groups from the international definition of genocide, which is contained in the Genocide Convention of 1948,[9] and in particular they have written that Joseph Stalin may have feared greater international scrutiny of the political killings that occurred in the country, such as the Great Purge;[10] however, this claim is not supported by evidence. The Soviet view was shared and supported by many diverse countries, and they were also in line with Raphael Lemkin's original conception,[b] and it was originally promoted by the World Jewish Congress.[12]

Historical genocides

[edit]Genocides before World War I

[edit]Raphael Lemkin applied the concept of genocide to a wide variety of events throughout human history. He and other scholars date the first genocides to prehistoric times.[13][14][15] Genocide is mentioned in various ancient sources including the Hebrew Bible, in which God commanded genocide (herem) against some of the Israelites' enemies, especially Amalek.[16][17] Genocide in the ancient world often consisted of the massacre of men and the enslavement or forced assimilation of women and children—often limited to a particular town or city rather than applied to a larger group.[18] Potential medieval examples are found in Europe, even though experts caution against applying a modern term like genocide to such events.[19] Overall, premodern examples that can be considered genocide were relatively uncommon.[20] Beginning in the early modern period, racial ideologies emerged as a more important factor.[21]

According to Frank Chalk, Helen Fein, and Kurt Jonassohn, if a dominant group of people had little in common with a marginalized group of people, it was easy for the dominant group to define the marginalized group as a subhuman group; the marginalized group might be labeled a threat that must be eliminated.[22]

The expansion of various European colonial powers, such as the British and the Spanish Empires, and the subsequent establishment of colonies on indigenous territory frequently involved acts of genocidal violence against indigenous groups in the Americas (including Brazil, Paraguay, and the United States), Australia, Africa, and Asia.[23] According to Lemkin, colonization was in itself "intrinsically genocidal", and he saw this genocide as a two-stage process, the first being the destruction of the indigenous population's way of life. In the second stage, the newcomers impose their way of life on the indigenous group.[24][25]

According to David Maybury-Lewis, imperial and colonial forms of genocide are enacted in two main ways, either through the deliberate clearing of territories of their original inhabitants to make them exploitable for purposes of resource extraction or colonial settlements, or through enlisting indigenous peoples as forced laborers in colonialist or imperialist projects of resource extraction.[26] The designation of specific events as genocidal is often controversial.[27]

During the 17th century Beaver Wars, the Iroquois destroyed several large tribal confederacies—including the Mohicans, Huron, Neutral, Erie, Susquehannock, and northern Algonquins—with extreme brutality. The exterminatory nature of the mode of warfare practised by the Iroquois caused some historians to label these events as acts of genocide.[28]

Genocides from World War I through World War II

[edit]

In 1915, one year after the outbreak of World War I, the concept of crimes against humanity was introduced into international relations for the first time, when the Allies of World War I sent a letter to the government of the Ottoman Empire, a member of the Central Powers, to protest against the late Ottoman genocides that were taking place within the empire, among them, the Armenian genocide, the Assyrian genocide, the Greek genocide, and the Great Famine of Mount Lebanon.[29] The Holocaust, the Nazi genocide of six million European Jews from 1941 to 1945 during the Second World War,[30][31] is the most studied genocide,[32] and it is also a prototype of genocide;[33] one of the most controversial questions among comparative scholars is the question of the Holocaust's uniqueness, which led to the Historikerstreit in West Germany during the 1980s,[34] and whether there exist historical parallels, which critics believe trivializes it.[35] It is considered to be the "worst case" paradigm of genocide.[36]

Genocide studies started as a side academic field of Holocaust studies, whose researchers associated genocide with the Holocaust and believed that Lemkin's definition of genocide was too broad.[33] In 1985, the United Nations' (UN) Whitaker Report cited the massacre of 100,000 to 250,000 Jews in more than 2,000 pogroms which occurred as part of the White Terror during the Russian Civil War as an act of genocide; it also suggested that consideration should be given to ecocide, ethnocide, and cultural genocide.[37]

Genocides from 1946 through 1999

[edit]The Genocide Convention was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 1948 and came into effect on 12 January 1951. After the necessary twenty countries became parties to the convention, it came into force as international law on 12 January 1951;[38] however, only two of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council were parties to the treaty, which caused the Convention to languish for over four decades.[39] During the Cold War era, mass atrocities were committed by communist regimes,[40] as well as by anti-communist/capitalist regimes,[41][42] among them the Indonesian mass killings of 1965–66, the 1971 Bangladesh genocide, the Cambodian genocide, the Guatemalan genocide and the East Timor genocide.[43] The Rwandan genocide gave an extra impetus to genocide studies in the 1990s.[44]

Genocides after 2000

[edit]

In The Guardian, David Alton, Helen Clark, and Michael Lapsley wrote that the reasons for the Rwandan genocide and crimes such as the Bosnian genocide of the Yugoslav Wars had been analyzed in-depth, and they also stated that genocide prevention had been extensively discussed. They described the analyses as producing "reams of paper [that] were dedicated to analyzing the past and pledging to heed warning signs and prevent genocide."[45]

A group of 34 non-governmental organizations and 31 individuals, calling themselves African Citizens, referred to the Rwanda: The Preventable Genocide report prepared by a panel headed by former Botswana president Quett Masire for the Organisation of African Unity, which later became the African Union.[46] African Citizens highlighted the sentences, commenting: "Indisputably, the most important truth that emerges from our investigation is that the Rwandan genocide could have been prevented by those in the international community who had the position and means to do so. ... The world failed Rwanda. ... [The United Nations] simply did not care enough about Rwanda to intervene appropriately."[47] Chidi Odinkalu, former head of the National Human Rights Commission of Nigeria, was among those involved with African Citizens.[48]

The ongoing Amhara genocide started in the early 1990s with the implementation of ethnic federalism under the TPLF-led ruling, and events of the Northern Ethiopia war (Tigray conflict) since 2020 that intensified the violence further with war crimes committed by the Tigray forces in both the Amhara & Afar regions. On 20 November 2021, Genocide Watch called for genocide in Ethiopia, predicted in the context of the war in Tigray and also the violence across the Oromia, and the Benishangul-Gumuz (Metekel) regions that worsened since 2018.[49] On 21 November, Odinkalu called for genocide prevention, stating: "We need to focus on an urgent programme of Genocide Prevention advocacy on Ethiopia NOW. It may be too late in 2 weeks, guys."[48] On 26 November, African Citizens and Alton, Clark, and Lapsley also called for the predicted genocide to be prevented.[45][47]

The Rohingya genocide is an ongoing genocide of the Muslim Rohingya people consisting of arson, rape, ethnic cleansing, and infanticide by the Burmese military. The genocide has so far consisted of two phases so: the first was a military crackdown that occurred from October 2016 to January 2017, and the second has been occurring since August 2017.[50][51]

The Chinese government has engaged in a series of human rights abuses against Uyghurs and other ethnic and religious minorities in Xinjiang.[52] Legislatures in several countries, including Canada,[53] the United Kingdom,[54] and France,[55] have passed non-binding motions describing China's actions as genocide. The United States officially denounced China's treatment of Uyghurs as a genocide.[56]

International prosecution

[edit]Ad hoc tribunals

[edit]In 1951, only two of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (UNSC) were parties to the convention, namely France and the Republic of China. The treaty was ratified by the Soviet Union in 1954, the United Kingdom in 1970, the People's Republic of China in 1983 (having replaced the Taiwan-based Republic of China on the UNSC in 1971), and the United States in 1988.[57] In the 1990s, the international law on the crime of genocide began to be enforced.[39]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

[edit]

In July 1995, Serbian forces killed more than 8,000[58][59][60] Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), mainly men and boys, both in and around the town of Srebrenica during the Bosnian War.[61][62] The killing was perpetrated by units of the Army of Republika Srpska which were under the command of General Ratko Mladić. The Secretary-General of the United Nations described the mass murder as the worst crime on European soil since the Second World War.[63][64] A paramilitary unit from Serbia known as the Scorpions, officially a part of the Serbian Interior Ministry until 1991, participated in the massacre,[65][66] along with several hundred Russian and Greek volunteers.[67][68]

In 2001, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia delivered its first conviction for the crime of genocide, against General Krstić for his role in the 1995 Srebrenica massacre (on appeal he was found not guilty of genocide but was instead found guilty of aiding and abetting genocide).[69]

In February 2007, the International Court of Justice returned a judgment in the Bosnian Genocide Case. It upheld the findings of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia that genocide had been committed in and around Srebrenica but did not find that genocide had been committed on the wider territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war. The court also ruled that Serbia was not responsible for the genocide nor was it responsible for "aiding and abetting it", although it ruled that Serbia could have done more to prevent the genocide and that Serbia failed to punish the perpetrators.[70] Before this ruling, the term Bosnian Genocide had been used by some academics[71][72][73] and human rights officials.[74]

In 2010, Vujadin Popović, Lieutenant Colonel and the Chief of Security of the Drina Corps of the Bosnian Serb Army, and Ljubiša Beara, Colonel and Chief of Security of the same army, were convicted of genocide, extermination, murder and persecution by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia for their role in the Srebrenica massacre and were each sentenced to life in prison.[75][76][77] In 2016 and 2017, Radovan Karadžić[78] and Ratko Mladić were sentenced for genocide.[79]

German courts handed down convictions for genocide during the Bosnian War. Novislav Djajic was indicted for his participation in the genocide, but the Higher Regional Court failed to find that there was sufficient certainty for a criminal conviction for genocide. Nevertheless, Djajic was found guilty of 14 counts of murder and one count of attempted murder.[80] At Djajic's appeal on 23 May 1997, the Bavarian Appeals Chamber found that acts of genocide were committed in June 1992, confined within the administrative district of Foca.[81] The Higher Regional Court (Oberlandesgericht) of Düsseldorf, in September 1997, handed down a genocide conviction against Nikola Jorgic, a Bosnian Serb from the Doboj region who was the leader of a paramilitary group located in the Doboj region. He was sentenced to four terms of life imprisonment for his involvement in genocidal actions that took place in regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina, other than Srebrenica.[82] On 29 November 1999, the Higher Regional Court (Oberlandesgericht) of Düsseldorf "condemned Maksim Sokolovic to 9 years in prison for aiding and abetting the crime of genocide and for grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions."[83]

Rwanda

[edit]The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) is a court under the auspices of the United Nations for the prosecution of offences committed during the Rwandan genocide during April and May 1994, commencing on 6 April. The ICTR was created on 8 November 1994 by the UN Security Council to resolve claims in Rwanda, or by Rwandan citizens in nearby states, between 1 January and 31 December 1994. For approximately 100 days from the assassination of President Juvénal Habyarimana on 6 April through mid-July, at least 800,000 people were killed according to a Human Rights Watch estimate.[84][85][86]

As of mid-2011, the ICTR had convicted 57 people and acquitted 8. Another ten persons were still on trial while one (Bernard Munyagishari) is awaiting trial; nine remain at large.[87] The first trial, of Jean-Paul Akayesu, ended in 1998 with his conviction for genocide and crimes against humanity.[88] Jean Kambanda, the interim prime minister during the genocide, pleaded guilty. This was the world's first conviction for genocide, as defined by the 1948 Convention.[89]

Cambodia

[edit]

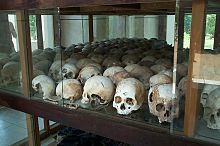

The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, Ta Mok, and others, perpetrated the mass killing of ideologically suspect groups, ethnic minorities such as ethnic Vietnamese, Chinese or Sino-Khmers, Chams, and Thais, former civil servants, former government soldiers, Buddhist monks, secular intellectuals and professionals, and former city dwellers. Khmer Rouge cadres who were defeated in factional struggles were also liquidated in purges. Man-made famine and slave labor resulted in many hundreds of thousands of deaths.[90] Craig Etcheson suggested that the death toll was between 2 and 2.5 million, with a most likely figure of 2.2 million. After spending five years excavating 20,000 grave sites, he concluded that "these mass graves contain the remains of 1,386,734 victims of execution."[91] Steven Rosefielde argued that the Khmer Rouge were not racist by claiming that they did not intend to exterminate ethnic minorities, and he also stated that the Khmer Rouge did not intend to exterminate the Cambodian people as a whole; in his view, the Khmer Rouge's brutality was the product of an extreme version of communist ideology.[92]

On 6 June 2003, the Cambodian government and the United Nations reached an agreement to set up the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), which would focus exclusively on crimes committed by the most senior Khmer Rouge officials during the period of Khmer Rouge rule of Cambodia from 1975 to 1979.[93] The judges were sworn in during early July 2006.[94][95][96] The investigating judges were presented with the names of five possible suspects by the prosecution on 18 July 2007:[97]

- Kang Kek Iew was formally charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity and detained by the Tribunal on 31 July 2007. He was indicted on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity on 12 August 2008.[98] His appeal was rejected on 3 February 2012, and he continued serving a sentence of life imprisonment.[99]

- Nuon Chea, a former prime minister, was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 19 September 2007. His trial began on 27 June 2011.[100][101] On 16 November 2018, he was sentenced to life in prison for genocide.[102]

- Khieu Samphan, a former head of state, was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 19 September 2007. His trial also began on 27 June 2011.[100][101] On 16 November 2018, he was sentenced to life in prison for genocide.[102]

- Ieng Sary, a former foreign minister, was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 12 November 2007. His trial began on 27 June 2011.[100][101] He died in March 2013.

- Ieng Thirith, wife of Ieng Sary and a former minister for social affairs, was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. She was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 12 November 2007. Proceedings against her have been suspended pending a health evaluation.[101][103]

Some of the international jurists and the Cambodian government disagreed over whether any other people should be tried by the Tribunal.[97]

International Criminal Court

[edit]The ICC can only prosecute crimes that were committed on or after 1 July 2002.[104][105]

Darfur, Sudan

[edit]

The racial conflict in Darfur, Sudan,[106] which started in 2003,[107][108] was declared a genocide by United States Secretary of State Colin Powell on 9 September 2004 in testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.[109][110] Since that time however, no other permanent member of the UN Security Council has followed suit. In January 2005, an International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur, authorized by UN Security Council Resolution 1564 of 2004, issued a report stating that "the Government of the Sudan has not pursued a policy of genocide."[111] Nevertheless, the Commission cautioned that "The conclusion that no genocidal policy has been pursued and implemented in Darfur by the Government authorities, directly or through the militias under their control, should not be taken in any way as detracting from the gravity of the crimes perpetrated in that region. International offences such as the crimes against humanity and war crimes that have been committed in Darfur may be no less serious and heinous than genocide."[111]

In March 2005, the Security Council formally referred the situation in Darfur to the ICC, taking into account the Commission report but without mentioning any specific crimes.[112] Two permanent members of the Security Council, the United States and China, abstained from the vote on the referral resolution.[113] As of his fourth report to the Security Council, the Prosecutor found "reasonable grounds to believe that the individuals identified [in the UN Security Council Resolution 1593] have committed crimes against humanity and war crimes", but did not find sufficient evidence to prosecute for genocide.[114]

In April 2007, the ICC issued arrest warrants against the former Minister of State for the Interior, Ahmad Harun, and a Janjaweed militia leader, Ali Kushayb, for crimes against humanity and war crimes.[115] On 14 July 2008, the ICC filed ten charges of war crimes against Sudan's president Omar al-Bashir, three counts of genocide, five of crimes against humanity, and two of murder. Prosecutors claimed that al-Bashir "masterminded and implemented a plan to destroy in substantial part" three tribal groups in Darfur because of their ethnicity.[116] On 4 March 2009, the ICC issued a warrant for al-Bashir's arrest for crimes against humanity and war crimes but not for genocide. This is the first warrant issued by the ICC against a sitting head of state.[117]

International Court of Justice

[edit]Ukraine

[edit]Two days after the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, on 26 February, Ukraine brought the case of Allegations of Genocide under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide before the International Court of Justice. The case followed false Russian accusations of genocide in Donbas which genocide scholars have described as accusation in a mirror as part of a campaign of genocide incitement.[118] The court is conducting an investigation of all allegations of genocide in Ukraine. In November 2022, Ukraine's Prosecutor General Andriy Kostin said that during the course of five proceedings on genocide by law enforcement, investigators had recorded "more than 300 facts that belong precisely to the definition of genocide".[119]

Rohingya

[edit]On 11 November 2019, The Gambia lodged an application to the International Court of Justice against Myanmar. It alleged that Myanmar has committed mass murder, rape, and destruction of communities against the Rohingya group in Rakhine state since about October 2016 and that those actions violated the Genocide Convention.[120]

Israel

[edit]On December 29, 2023, South Africa filed an application instituting proceedings with the International Court of Justice against Israel, alleging that it had violated its obligations under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (the "Genocide Convention") during its 2023 offensive in the Gaza Strip.[121] South Africa's standing is based on the erga omnes partes nature of the Genocide Convention, which allows and obligates States Parties to the convention to take measures to prevent and punish the crime of genocide. South Africa requested indication of provisional measures by the court, including that Israel end its military operations, to "protect against further, severe and irreparable harm to the rights of the Palestinian people under the Genocide Convention", triggering an urgent preliminary hearing. Public hearings on the provisional measures question were held on January 11 (oral arguments by South Africa) and January 12 (oral arguments by Israel), respectively.[122]

See also

[edit]- Accusation in a mirror

- Anti-communist mass killings

- Anti-Mongolianism

- Black genocide in the United States – the notion that African Americans have been subjected to genocide throughout their history because of racism against African Americans, an aspect of racism in the United States

- Crimes against humanity

- Criticism of communist party rule

- Democide

- Ethnic cleansing

- Ethnic conflict

- Ethnic violence

- Ethnocentrism

- Ethnocide

- Far-left politics

- Far-right politics

- Far-right subcultures

- Genocide denial

- Genocide recognition politics

- Genocide of Christians by the Islamic State

- Genocide of Yazidis by the Islamic State

- Hate crime

- List of ethnic cleansing campaigns

- List of genocides

- Mass killings under communist regimes

- Nativism (politics)

- Persecution of Shias by the Islamic State

- Political cleansing of population – an aspect of political violence

- Population transfer

- Racism

- Religious intolerance

- Religious discrimination

- Religious persecution

- Religious violence

- Sectarian violence

- Supremacism

- Terrorism

- War crime

- Xenophobia

Notes

[edit]- ^ Defined under the Genocide Convention as a "national, ethnical, racial, or religious group."

- ^ By 1951, Lemkin was saying that the Soviet Union was the only state that could be indicted for genocide; his concept of genocide, as it was outlined in Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, covered Stalinist deportations as genocide by default, and differed from the adopted Genocide Convention in many ways. From a 21st-century perspective, its coverage was very broad, and as a result, it would classify any gross human rights violation as a genocide, and many events that were deemed genocidal by Lemkin did not amount to genocide. As the Cold War began, this change was the result of Lemkin's turn to anti-communism in an attempt to convince the United States to ratify the Genocide Convention.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 12 January 1951. Archived from the original on 11 December 2005. Note: "ethnical", although unusual, is found in several dictionaries.

- ^ Towner 2011, pp. 625–638; Lang 2005, pp. 5–17: "On any ranking of crimes or atrocities, it would be difficult to name an act or event regarded as more heinous. Genocide arguably appears now as the most serious offense in humanity's lengthy—and, we recognize, still growing—list of moral or legal violations."; Gerlach 2010, p. 6: "Genocide is an action-oriented model designed for moral condemnation, prevention, intervention or punishment. In other words, genocide is a normative, action-oriented concept made for the political struggle, but in order to be operational it leads to simplification, with a focus on government policies."; Hollander 2012, pp. 149–189: "... genocide has become the yardstick, the gold standard for identifying and measuring political evil in our times. The label 'genocide' confers moral distinction on its victims and indisputable condemnation on its perpetrators."

- ^ Schabas, William A. (2000). Genocide in International Law: The Crimes of Crimes (PDF) (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 9, 92, 227. ISBN 0-521-78262-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2024.

- ^ Straus, Scott (2022). Graziosi, Andrea; Sysyn, Frank E. (eds.). Genocide: The Power and Problems of a Concept. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 223, 240. ISBN 978-0-2280-0951-1.

- ^ Rugira, Lonzen (20 April 2022). "Why Genocide is "the crime of crimes"". Pan African Review. Archived from the original on 13 June 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ a b Anderton, Charles H.; Brauer, Jurgen, eds. (2016). Economic Aspects of Genocides, Other Mass Atrocities, and Their Prevention. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-937829-6.

- ^ Kakar, Mohammed Hassan (1995). Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982. University of California Press. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-0-5209-1914-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ Chalk & Jonassohn 1990.

- ^ Staub 1989, p. 8.

- ^ Gellately & Kiernan 2003, p. 267.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2005.

- ^ Schabas 2009, p. 160: "Rigorous examination of the travaux fails to confirm a popular impression in the literature that the opposition to the inclusion of political genocide was some Soviet machination. The Soviet views were also shared by a number of other States for whom it is difficult to establish any geographic or social common denominator: Lebanon, Sweden, Brazil, Peru, Venezuela, the Philippines, the Dominican Republic, Iran, Egypt, Belgium, and Uruguay. The exclusion of political groups was originally promoted by a non-governmental organization, the World Jewish Congress, and it corresponded to Raphael Lemkin's vision of the nature of the crime of genocide."

- ^ Naimark 2017, p. vii.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 31.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 11.

- ^ Naimark 2017, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, pp. 39, 50.

- ^ Fraser 2010, p. 277.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 47.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 55.

- ^ Jones 2006, p. 3: "The difficulty, as Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn pointed out in their early study, is that such historical records as exist are ambiguous and undependable. While history today is generally written with some fealty to 'objective' facts, most previous accounts aimed rather to praise the writer's patron (normally the leader) and to emphasize the superiority of one's own gods and religious beliefs."

- ^ Jones 2010, p. 139.

- ^ Moses 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Forge 2012, p. 77.

- ^ Maybury-Lewis 2002, p. 48.

- ^ Hitchcock & Koperski 2008, pp. 577–582.

- ^ Blick, Jeremy P. (3 August 2010). "The Iroquois practice of genocidal warfare (1534-1787)". Journal of Genocide Research. 3 (3): 405–429. doi:10.1080/14623520120097215. S2CID 71358963. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ 1915 declaration:

- Affirmation of the United States Record on the Armenian Genocide Resolution, 106th Congress, 2nd Session, House of Representatives, archived from the original on 14 April 2016, retrieved 23 January 2021;

- Affirmation of the United States Record on the Armenian Genocide Resolution (Introduced in House of Representatives), 109th Congress, 1st Session, 15 September 2005, archived from the original on 3 July 2016, retrieved 23 January 2021; H.res.316, House Committee/Subcommittee:International Relations actions, 14 June 2005, archived from the original on 3 July 2016, retrieved 15 September 2005: Status: Ordered to be Reported by the Yeas and Nays: 40 – 7.

- The French, British and Russian joint declaration (original source of the telegram), Washington, D.C.: The Department of State, 24 May 1915, archived from the original on 27 January 2024, retrieved 4 June 2017

- ^ Landau, Ronnie S. (2016). The Nazi Holocaust: Its History and Meaning (3rd ed.). I. B. Tauris. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-85772-843-2.

- ^ Herf, Jeffrey C. (2024). "The Long Term and the Short Term: Antisemitism and the Holocaust". In Weitzman, Mark; Williams, Robert J.; Wald, James (eds.). The Routledge History of Antisemitism (1st ed.). Abingdon and New York: Routledge. p. 278. doi:10.4324/9780429428616. ISBN 978-1-138-36944-3.

- ^ Jongman 1996.

- ^ a b Moses 2010, p. 21.

- ^ Stone 2010, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Rosenbaum 2001, "Foreword".

- ^ Rosenbaum, Alan S. "Philosophical Reflections on Genocide and the Claim About the Uniqueness of the Holocaust". Boston University. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Bartrop & Jacobs 2014, p. 1106.

- ^ Akande et al. 2018, p. 64.

- ^ a b Hoffman 2010, p. 260.

- ^ Bellamy 2012, "The Cold War Struggle (2): Communist Atrocities".

- ^ Farid 2005.

- ^ Bellamy 2012, "The Cold War Struggle (1): Capitalist Atrocities".

- ^ Fein 1993.

- ^ Bloxham & Moses 2010, p. 2.

- ^ a b Clark, Helen; Lapsley, Michael; Alton, David (26 November 2021). "The warning signs are there for genocide in Ethiopia – the world must act to prevent it". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ International panel of eminent personalities (21 January 2004). "Rwanda: The Preventable Genocide" (PDF). African Union. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ a b Mustapha, Ogunsakin (26 November 2021). "Group warns UN over imminent genocide in Ethiopia". Citizens' Gavel. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ a b Odinkalu, Chidi (21 November 2021). "Lessons from Rwanda: dangers of an Ethiopian genocide increase as rebels threaten Addis". Eritrea Hub. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Ross, Eric; Hill, Nat (20 November 2021). "Genocide Emergency: Ethiopia". Genocide Watch. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "World Court Rules Against Myanmar on Rohingya". Human Rights Watch. 23 January 2020. Archived from the original on 22 April 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ "Myanmar's Rohingya Crisis Enters a Dangerous New Phase". www.crisisgroup.org. 7 December 2017. Archived from the original on 10 September 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ "Uighurs: 'Credible case' China carrying out genocide". BBC News. 8 February 2021. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021.

- ^ Jones, Ryan Patrick (22 February 2021). "MPs vote to label China's persecution of Uighurs a genocide". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 15 August 2024.

A substantial majority of MPs — including most Liberals who participated — voted in favour of a Conservative motion that says China's actions in its western Xinjiang region meet the definition of genocide set out in the 1948 United Nations Genocide Convention. ... The final tally was 266 in favour and zero opposed. Two MPs formally abstained.

- ^ Hefffer, Greg (22 April 2021). "House of Commons declares Uighurs are being subjected to genocide in China". Sky News. Archived from the original on 16 February 2024.

- ^ "French Parliament Denounces China's Uyghur 'Genocide'". Barron's. Agence Press-France. 20 January 2022. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024.

- ^ Gordon, Michael R. (19 January 2021). "U.S. Says China Is Committing 'Genocide' Against Uighur Muslims". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021.

- ^ Bachman 2017: "However, the US failed to ratify the treaty until November 25, 1988."

- ^ Bookmiller, Kirsten Nakjavani (2008). The United Nations. Infobase Publishing. p. 81. ISBN 978-1438102993. Retrieved 4 August 2013 – via Google Books.

- ^ Paul, Christopher; Clarke, Colin P.; Grill, Beth (2010). Victory Has a Thousand Fathers: Sources of Success in Counterinsurgency. Rand Corporation. p. 25. ISBN 978-0833050786. Retrieved 4 August 2013 – via Google Books.

- ^ Simons, Marlise (31 May 2011). "Mladic Arrives in The Hague". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 April 2024.

- ^ "Srebrenica-Potočari: spomen obilježje i mezarje za žrtve genocida iz 1995 godine. Liste žrtava prema prezimenu" [Srebrenica-Potocari: Memorial and Cemetery for the victims of the genocide of 1995. Lists of victims by surname] (in Bosnian). 1995. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014.

- ^ "ICTY: The Conflicts". International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "Secretary-General Kofi Annan's message to the ceremony marking the tenth anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre in Potocari-Srebrenica". UN Press Release SG/SM/9993UN, 11/07/2005. United Nations. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ^ Institute for War and Peace Reporting, Tribunal Update: Briefly Noted (TU No 398, 18 March 2005). "Institute for War & Peace Reporting - IWPR".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Williams, Daniel. "Srebrenica Video Vindicates Long Pursuit by Serb Activist". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 August 2023. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ "ICTY – Kordic and Cerkez Judgement – 3. After the Conflict" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2024. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Naimark, Norman M. (2011). Memories of Mass Repression: Narrating Life Stories in the Aftermath of Atrocity. Transaction Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 978-1412812047. Retrieved 4 August 2013 – via Google Books.

- ^ Smith, Helena (5 January 2003). "Greece faces shame of role in Serb massacre". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024.

- ^ The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia found in Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Trial Chamber I – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2001) ICTY8 (2 August 2001) that genocide had been committed. (see paragraph 560 for the name of the group in English on whom the genocide was committed). The judgement was upheld in Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Appeals Chamber – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2004) ICTY 7 (19 April 2004)

- ^ Max, Arthur (26 February 2007). "Court: Serbia failed to prevent genocide". The San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 10 August 2007.

- ^ "HNPG 036P (or 033T) History: Bosnian Genocide In the Historical Perspective". University of California Riverside. 2003. Archived from the original on 16 May 2007.

- ^ "Winter 2007 Honors Courses". University of California Riverside. 2007. Archived from the original on 10 August 2007.

- ^ "Winter 2008 Honors Courses". University of California Riverside. 2007. Archived from the original on 29 October 2007.

- ^ "Milosevic to Face Bosnian Genocide Charges". Human Rights Watch. 11 December 2001. Archived from the original on 2 December 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ "Seven convicted over 1995 Srebrenica massacre". CNN. 10 June 2010. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023.

- ^ "Life for Bosnian Serbs over genocide at Srebrenica". BBC News. 10 June 2010. Archived from the original on 13 July 2024.

- ^ Waterfield, Bruno (10 June 2010). "Bosnian Serbs convicted of genocide over Srebrenica massacre". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Radovan Karadzic sentenced to 40-year imprisonment for Srebrenica genocide, war crimes". The Hindu. Reuters. 24 March 2016. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020.

- ^ "UN hails conviction of Mladic, the 'epitome of evil,' a momentous victory for justice". UN News Centre. 22 November 2017. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "Novislav Djajic". Trial Watch. 19 June 2013. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Trial Chamber I – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2001) ICTY8 (2 August 2001), The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, paragraph 589. citing Bavarian Appeals Court, Novislav Djajic case, 23 May 1997, 3 St 20/96, section VI, p. 24 of the English translation.

- ^ Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf, "Public Prosecutor v Jorgic", 26 September 1997 (Trial Watch) Nikola Jorgic Archived 24 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Trial watch Maksim Sokolovic Archived 6 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Des Forges, Alison (1999). "'Leave None to Tell the Story'" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2024. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ "Joseph Sebarenzi Shares his Perspective on the Genocide in Rwanda in Two Lectures". BYU Humanities. BYU College of Humanities. 20 November 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2024. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ Maron, Jeremy (2022). "What led to the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda?". Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Archived from the original on 13 August 2024. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ "United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda: Status of Cases". ICTR. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011.

- ^ "United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda: Status of Cases". ICRT. Archived from the original on 2 December 2012.

- ^ "Rwanda: The First Conviction for Genocide". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 5 April 2021. Archived from the original on 12 June 2024. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ Sliwinski, Marek (1995). Le génocide khmer rouge: une analyze démographique [The Khmer Rouge Genocide: A Demographic Analysis] (in French). Harmattan. p. 82. ISBN 978-2-7384-3525-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sharp, Bruce (1 April 2005). "Counting Hell: The Death Toll of the Khmer Rouge Regime in Cambodia". Mekong.Net. Mekong Network. Archived from the original on 22 June 2024. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ Rosefielde, Steven (2009). Red Holocaust. Routledge. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-415-77757-5.

- ^ "Resolution adopted by the General Assembly: 57/228 Khmer Rouge trials B1" (PDF). United Nations General Assembly. 22 May 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Doyle, Kevin (26 July 2007). "Putting the Khmer Rouge on Trial". Time. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ MacKinnon, Ian (7 March 2007). "Crisis talks to save Khmer Rouge trial". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 November 2007.

- ^ "The Khmer Rouge Trial Task Force". Royal Cambodian Government. Archived from the original on 3 April 2005.

- ^ a b Buncombe, Andrew (11 October 2011). "Judge quits Cambodia genocide tribunal". The Independent. London.

- ^ Munthit, Ker (12 August 2008). "Cambodian tribunal indicts Khmer Rouge jailer". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ "Kaing Guek Eav alias Duch Sentenced to Life Imprisonment by the Supreme Court Chamber". Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. 3 February 2012. Archived from the original on 11 August 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ a b c "Case 002". Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d "002/19-09-2007: Closing Order" (PDF). Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. 15 September 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ a b "UN genocide adviser welcomes historic conviction of former Khmer Rouge leaders". UN News. 16 November 2018. Archived from the original on 19 July 2024. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "002/19-09-2007: Decision on immediate appeal against Trial Chamber's order to release the accused Ieng Thirith" (PDF). Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. 13 December 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ "Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: Article 11". United Nations Office of Legal Affairs. 17 July 1999. Archived from the original on 23 August 2024. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ "ICC: About the court". ICC. Archived from the original on 9 March 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ^ "Crisis in Sudan | Janjaweed Militia | PBS". PBS NewsHour. PBS. 28 January 2007. Archived from the original on 28 January 2007.

- ^ Mutua, Makau (14 July 2004). "Racism at root of Sudan's Darfur crisis". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 16 February 2024.

- ^ "Darfur's Sorrow: A History of Destruction and Genocide. -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia". 8 December 2009. Archived from the original on 8 December 2009.

- ^ "Powell Declares Killing in Darfur 'Genocide'". The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer. PBS. 9 September 2004. Archived from the original on 11 September 2004.

- ^ Leung, Rebecca (8 October 2004). "Witnessing Genocide in Sudan". CBS News. Archived from the original on 16 June 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Report of the International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur to the United Nations Secretary-General" (PDF). United Nations. 25 January 2005. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ "Security Council Resolution 1593 (2005)" (PDF). United Nations Security Council. 31 March 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2005.

- ^ "Security Council Refers Situation in Darfur, Sudan, to Prosecutor of International Criminal Court". UN Press Release SC/8351. United Nations. 31 March 2005. Archived from the original on 13 March 2024.

- ^ "Fourth Report of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, to the Security Council pursuant to UNSC 1593 (2005)" (PDF). International Criminal Court (ICC). 14 December 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2007.

- ^ "Statement by Mr. Luis Moreno Ocampo, Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, to the United Nations Security Council pursuant to UNSCR 1593 (2005)" (PDF). International Criminal Court (ICC). 5 June 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2008.

- ^ Walker, Peter; Sturcke, James (14 July 2008). "Darfur genocide charges for Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ Staff (4 March 2009). "Warrant issued for Sudan's leader". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019.

- ^ "Independent Legal Analysis of the Russian Federation's Breaches of the Genocide Convention in Ukraine and the Duty to Prevent" (PDF). New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy; Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights. 27 May 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 June 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "Ukrainian law enforcement officers record more than 300 cases of genocide – top prosecutor". Ukrinform. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ "Factbox: Myanmar on trial for Rohingya genocide – the legal cases". Reuters. 1 November 2019. Archived from the original on 21 February 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Application instituting proceedings and request for the indication of provisional measures. Document Number 192-20231228-APP-01-00-EN". International Court of Justice. Archived from the original on 11 August 2024.

- ^ "Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in the Gaza Strip (South Africa v. Israel)". International Court of Justice. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Akande, Dapo; Higgins, Rosalyn; Sivakumaran, Sandesh; Webb, Philippa (2018). Oppenheim's International Law: United Nations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-192-53718-8 – via Google Books.

- Bachman, Jeffrey S. (2017). The United States and Genocide: (Re)Defining the Relationship with Genocide (E-book ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-69216-8 – via Google Books.

- Bartrop, Paul R.; Jacobs, Steven Leonard, eds. (2014). Modern Genocide: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-610-69364-6 – via Google Books.

- Bellamy, Alex J. (2012). Massacres and Morality: Mass Atrocities in an Age of Civilian Immunity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-28842-7.

- Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (2010). "Editors' Introduction: Changing Themes in the Study of Genocide". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–15. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199232116.013.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

- Chalk, Frank; Jonassohn, Kurt (1990). The History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04446-1.

- Farid, Hilmar (March 2005). "Indonesia's original sin: mass killings and capitalist expansion, 1965–66". Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 6 (1). Routledge: 3–16. doi:10.1080/1462394042000326879. ISSN 1464-9373. S2CID 145130614.

- Fein, Helen (October 1993). "Revolutionary and Antirevolutionary Genocides: A Comparison of State Murders in Democratic Kampuchea, 1975 to 1979, and in Indonesia, 1965 to 1966". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 35 (4). Cambridge University Press: 796–823. doi:10.1017/S0010417500018715. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 179183. S2CID 145561816.

- Forge, John (2012). Designed to Kill: The Case Against Weapons Research. Springer. ISBN 978-9400757356.

- Fraser, James E. (2010). "Early Medieval Europe: The Case of Britain and Ireland". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 259–279. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199232116.013.0014. ISBN 978-0-19-161361-6.

- Gellately, Robert; Kiernan, Ben (2003). The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52750-7 – via Google Books.

- Gerlach, Christian (2010). Extremely Violent Societies: Mass Violence in the Twentieth-Century World. Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-139-49351-2 – via Google Books.

- Hitchcock, Robert K.; Koperski, Thomas E. (2008). "Genocides against Indigenous Peoples". In Stone, Dan (ed.). The Historiography of Genocide. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 577–618. ISBN 9781403992192.

- Hoffman, Stefan-Ludwig (2010). Human Rights in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-49410-6 – via Google Books.

- Hollander, Paul (1 July 2012). "Perspectives on Norman Naimark's Stalin's Genocides". Journal of Cold War Studies. 14 (3): 149–189. doi:10.1162/JCWS_a_00250. S2CID 57560838.

- Irvin-Erickson, Douglas (2023). "The history of Rapha'l Lemkin and the UN Genocide Convention". In Simon, David J.; Kahn, Leora (eds.). Handbook of Genocide Studies. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 7–26. doi:10.4337/9781800379343.00009. ISBN 9781800379336.

- Jones, Adam (2006). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Publishers. ISBN 978-0-415-35385-4 – via Google Books. Excerpts Chapter 1: Genocide in prehistory, antiquity, and early modernity Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Jones, Adam (2010). "3. Genocides of Indigenous Peoples". Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415486187.

- Jongman, Albert J., ed. (1996). Contemporary Genocides: Causes, Cases, Consequences. Leiden, Netherlands: Interdisciplinary Research Program on the Root Causes of Human Rights Violations.

- Lang, Berel (2005). "The Evil in Genocide". Genocide and Human Rights: A Philosophical Guide. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 5–17. doi:10.1057/9780230554832_1. ISBN 978-0-230-55483-2.

- Lemos, T. M.; Taylor, Tristan S.; Kiernan, Ben (2023). "Introduction to Volume I". In Kiernan, Ben; Lemos, T. M.; Taylor, Tristan S. (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Genocide. Vol. 1: Genocide in the Ancient, Medieval and Premodern Worlds. Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–56. doi:10.1017/9781108655989.003. ISBN 978-1-108-65598-9.

- Maybury-Lewis, David (2002). "Genocide against Indigenous peoples". Annihilating Difference: The Anthropology of Genocide. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520230293.

- Moses, A. Dirk (2004). Genocide and Settler Society: Frontier Violence and Stolen Indigenous Children in Australian History. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1571814104.

- Moses, A. Dirk (2010). "Raphael Lemkin, Culture, and the Concept of Genocide". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 19ff. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199232116.013.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

- Naimark, Norman M. (2017). Genocide: A World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-976527-0.

- Rosenbaum, Alan S. (2001). Is the Holocaust Unique? Perspectives on Comparative Genocide (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-367-00714-0.

- Schabas, William (2000). Genocide in International Law: The Crimes of Crimes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78790-1.

- Schabas, William A. (2009). Genocide in International Law: The Crime of Crimes (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-71900-1.

- Staub, Ervin (1989). The Roots of Evil: The Origins of Genocide and Other Group Violence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42214-7 – via Google Books.

- Stone, Dan (2010). Histories of the Holocaust. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956679-2.

- Towner, Emil B. (2011). "Quantifying Genocide: What Are We Really Counting (On)?". JAC. 31 (3/4): 625–638. ISSN 2162-5190. JSTOR 41709663.

- Weiss-Wendt, Anton (December 2005). "Hostage of Politics: Raphael Lemkin on 'Soviet Genocide'". Journal of Genocide Research. 7 (4). Routledge: 551–559. doi:10.1080/14623520500350017. ISSN 1462-3528. S2CID 144612446.

Further reading

[edit]- Andreopoulos, George J. (1997). Genocide: Conceptual and Historical Dimensions. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1616-5 – via Google Books.

- Asociación Americana para el Avance de la Ciencia (1999). "Metodología intermuestra I: introducción y resumen" [Inter-sample methodology I: introduction and summary]. Instrumentes Legales y Operativos Para el Funcionamiento de la Comisión Para el Esclarecimiento Histórico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 May 2013.

- Bonwick, James (1870). The Last of the Tasmanians; or, The Black War of Van Diemen's Land. London: Sampson Low, Son, & Marston.

- Braudel, Fernand (1984). Civilization and Capitalism. Vol. III: The Perspective of the World. (in French 1979).

- Chakma, Kabita; Hill, Glen (2013). "Indigenous Women and Culture in the Colonized Chittagong Hills Tracts of Bangladesh". In Visweswaran, Kamala (ed.). Everyday Occupations: Experiencing Militarism in South Asia and the Middle East. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 132–157. ISBN 978-0812244878.

- Clarke, Michael Edmund (2004). In the Eye of Power: China and Xinjiang from the Qing Conquest to the 'New Great Game' for Central Asia, 1759–2004 (PDF) (Thesis). Griffith University, Brisbane: Dept. of International Business & Asian Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008.

- Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico: Agudización (1999). "Agudización de la Violencia y Militarización del Estado (1979–1985)" [Intensification of Violence and Militarization of the State (1979–1985)]. Guatemala: Memoria del Silencio (in Spanish). Programa de Ciencia y Derechos Humanos, Asociación Americana del Avance de la Ciencia. Archived from the original on 6 May 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- Cribb, Robert; Coppel, Charles (2009). "A genocide that never was: explaining the myth of anti-Chinese massacres in Indonesia, 1965–66". Journal of Genocide Research. 11 (4). Taylor & Francis: 447–465. doi:10.1080/14623520903309503. ISSN 1469-9494. S2CID 145011789.

- Cooper, Allan D. (3 August 2006). "Reparations for the Herero Genocide: Defining the limits of international litigation". African Affairs. 106 (422): 113–126. doi:10.1093/afraf/adl005.

- Cronon, William (1983). Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. Macmillan. ISBN 0-8090-1634-6.

- Crowe, David M. (2013). "War Crimes and Genocide in History". In Crowe, David M. (ed.). Crimes of State Past and Present: Government-Sponsored Atrocities and International Legal Responses. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1317986812 – via Google Books.

- Crosby, Alfred W. (1986). Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45690-8.

- Curthoys, Ann (2008). "Genocide in Tasmania". In Moses, A. Dirk (ed.). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-452-4 – via Google Books.

- Diamond, Jared (1993). The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-098403-8.

- Finnegan, Richard B.; McCarron, Edward (2000). Ireland: Historical Echoes, Contemporary Politics. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-3247-5 – via Google Books.

- Frank, Matthew James (2008). Expelling the Germans: British opinion and post-1945 population transfer in context. Oxford historical monographs. Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-19-923364-9.

- Friedrichsmeyer, Sara; Lennox, Sara; Zantop, Susanne (1998). The Imperialist Imagination: German Colonialism and Its Legacy. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-06682-7 – via Google Books.

- Glynn, Ian; Glynn, Jenifer (2004). The Life and Death of Smallpox. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Gammer, M. (2006). The Lone Wolf and the Bear: Three Centuries of Chechen Defiance of Russian Rule. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-748-4 – via Google Books.

- Gray, Richard A. (1994). "Genocide in the Chittagong Hill tracts of Bangladesh". Reference Services Review. 22 (4): 59–79. doi:10.1108/eb049231.

- Goble, Paul (15 July 2005). "Circassians demand Russian apology for 19th century genocide". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 5 January 2007.

- Jaimoukha, Amjad (2004). The Chechens: A Handbook. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-35643-2 – via Google Books.

- Kennedy, Liam (2016). Unhappy the Land: The Most Oppressed People Ever, the Irish?. Dublin: Irish Academic Press. ISBN 9781785370472.

- Kiernan, Ben (2002). "Cover-up and Denial of Genocide: Australia, the USA, East Timor, and the Aborigines" (PDF). Critical Asian Studies. 34 (2): 163–92. doi:10.1080/14672710220146197. S2CID 146339164. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2003.

- ——— (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10098-3.

- Kinealy, Christine (1995). This Great Calamity: The Irish Famine 1845–52. Gill & Macmillan. p. 357. ISBN 978-1-57098-034-3.

- King, Michael (2000). Moriori: A People Rediscovered. Viking. ISBN 978-0-14-010391-5 – via Google Books.

- Kopel, Dave; Gallant, Paul; Eisen, Joanne D. (11 April 2003). "A Moriori Lesson: a brief history of pacifism". National Review Online. Archived from the original on 11 April 2003.

- Levene, Mark (2005). Genocide in the Age of the Nation State: Volume 2: The Rise of the West and Coming Genocide. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-057-4 – via Google Books.

- Levene, Mark (2008). "Empires, Native Peoples, and Genocides". In Moses, A. Dirk (ed.). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. Oxford and New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 183–204. ISBN 978-1-84545-452-4 – via Google Books.

- Madley, Benjamin (2008). "From Terror to Genocide: Britain's Tasmanian Penal Colony and Australia's History Wars". Journal of British Studies. 47 (1): 77–106. doi:10.1086/522350. JSTOR 10.1086/522350. S2CID 146190611.

- McCarthy, Justin (1995), Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims, 1821–1922, Darwin

- Mey, Wolfgang, ed. (1984). Genocide in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh (PDF). Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA).

- Moshin, A. (2003). The Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh: On the Difficult Road to Peace. Boulder, Col.: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Niewyk, Donald L.; Nicosia, Francis R. (2000). The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust. Columbia University Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780231112000.

The Holocaust is commonly defined as the murder of more than 5,000,000 Jews by the Germans in World War II.

- O'Brien, Sharon (2004). "The Chittagong Hill Tracts". In Shelton, Dinah (ed.). Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. Macmillan Library Reference. pp. 176–77.

- Ó Gráda, Cormac (2000). Black '47 and Beyond: The Great Irish Famine in History, Economy, and Memory. Princeton University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-691-07015-5.

- Olusoga, David; Erichsen, Casper W. (2010). The Kaiser's Holocaust: Germany's Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0571231416.

- Perdue, Peter C. (2005). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia. Cambridge, MA; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01684-2.

- Robins, Nicholas; Jones, Adam (2009). Genocides by the Oppressed. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-22077-6 – via Google Books.

- Roy, Rajkumari (2000). Land Rights of the Indigenous Peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

- Rubinstein, W. D. (2004). Genocide: A History. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-582-50601-5 – via Google Books.

- Rummel, Rudolph J. (1998). Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-8258-4010-5 – via Google Books.

- Sarkin-Hughes, Jeremy (2008). Colonial Genocide and Reparations Claims in the 21st Century: The Socio-Legal Context of Claims under International Law by the Herero against Germany for Genocide in Namibia, 1904–1908. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-36257-6 – via Google Books.

- Sheriff, Abdul; Ferguson, Ed (1991). Zanzibar under colonial rule. J. Currey. ISBN 978-0-8214-0996-1 – via Google Books.

- Sommer, Tomasz (2010). "Execute the Poles: The Genocide of Poles in the Soviet Union, 1937–1938. Documents from Headquarters". The Polish Review. 55 (4): 417–436. doi:10.2307/27920673. JSTOR 27920673. S2CID 151099905.

- Speller, Ian (2007). "An African Cuba? Britain and the Zanzibar Revolution, 1964". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 35 (2): 1–35. doi:10.1080/03086530701337666. S2CID 159656717.

- Stannard, David E. (1993). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

... estimated population for the year 1769 ... Nationwide by this time only about one-third of one percent of America's population—250,000 out of 76,000,000 people—were natives. The worst human holocaust the world had ever witnessed ... finally had leveled off. There was, at last, almost no one left to kill.

- Tan, Mely G. (2008). Etnis Tionghoa di Indonesia: Kumpulan Tulisan [Ethnic Chinese in Indonesia: A Collection of Writings] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia. ISBN 978-979-461-689-5.

- van Bruineßen, Martin (1994), "Genocide in Kurdistan? The suppression of the Dersim rebellion in Turkey (1937–38) and the chemical war against the Iraqi Kurds (1988)", in Andreopoulos, George J. (ed.), Conceptual and historical dimensions of genocide (PDF), University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 141–70, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2013, retrieved 24 December 2013

- Vanthemsche, Guy (2012). Belgium and the Congo, 1885–1980. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521194211 – via Google Books.

- Weisbord, Robert G. (2003). "The King, the Cardinal, and the Pope: Leopold II's genocide in the Congo and the Vatican". Journal of Genocide Research. 5: 35–45. doi:10.1080/14623520305651. S2CID 73371517.

- Woodham-Smith, Cecil (1964). "The Great Hunger: Ireland 1845–1849". Signet: New York: 19.

- Wright, Ronald (2004). A Short History of Progress. Toronto: House of Anansi Press. ISBN 978-0-88784-706-6.