John L. Sullivan

John L. Sullivan | |

|---|---|

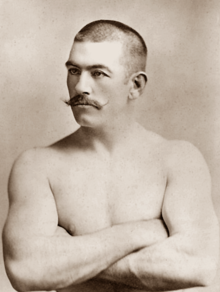

Sullivan in 1882 | |

| Born | John Lawrence Sullivan October 15, 1858 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | February 2, 1918 (aged 59) Abington, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Other names |

|

| Statistics | |

| Weight(s) | |

| Height | 5 ft 10+1⁄2 in (179 cm)[1] |

| Reach | 74 in (188 cm) |

| Stance | Orthodox |

| Boxing record | |

| Total fights | 46 |

| Wins | 42 |

| Wins by KO | 32 |

| Losses | 1 |

| Draws | 3 |

John Lawrence Sullivan (October 15, 1858 – February 2, 1918), known simply as John L. among his admirers, and dubbed the "Boston Strong Boy" by the press, was an American boxer. He is recognized as the first heavyweight champion of gloved boxing, de facto reigning from February 7, 1882, to September 7, 1892. He is also generally recognized as the last heavyweight champion of bare-knuckle boxing under the London Prize Ring Rules, being a cultural icon of the late 19th century America, arguably the first boxing superstar and one of the world's highest-paid athletes of his era. Newspapers' coverage of his career, with the latest accounts of his championship fights often appearing in the headlines, and as cover stories, gave birth to sports journalism in the United States and set the pattern internationally for covering boxing events in media, and photodocumenting the prizefights.[2]

Early life

[edit]Sullivan was born on October 15, 1858, in the Roxbury[3][4] neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, to Irish immigrant parents, Michael Sullivan from Abbeydorney, County Kerry and Catherine Kelly from Athlone, County Westmeath.

He attended public schools in his native Boston, attending the Dwight Grammar School and performing well academically.[5]

Sullivan's parents aspired for their son to enter the priesthood as a Catholic priest.[5] To this end Sullivan enrolled at Boston College circa 1875 but after only a few months he turned to playing baseball professionally, earning the substantial sum of $30 to $40 a week for his efforts.[5] As Sullivan recalled in 1883:

"I threw my books aside and gave myself up to it. This is how I got into the base-ball profession, and I left school for good and all. From the base-ball business I drifted into boxing and pugilism."[5]

Boxing career

[edit]As a professional fighter Sullivan was nicknamed The Boston Strongboy. As a youth he was arrested several times for participating in bouts where the sport was outlawed. He went on exhibition tours offering people money to fight him. Sullivan won more than 450 fights in his career.

There is some controversy among boxing historians over whether Sullivan had sparred with black boxer James Young at Schieffelin Hall in Tombstone, Arizona, in 1882. It is significant because Sullivan insisted that he never fought a black boxer. If it did occur, Sullivan possibly had a brief sparring session with the resident from Tombstone and did not regard it seriously as a bout.[6]

In 1883–84 Sullivan went on a coast-to-coast tour by train with five other boxers. They were scheduled to hold 195 fights in 136 different cities and towns over 238 days. To help promote the tour, Sullivan announced that he would box anyone at any time during the tour under the Queensberry Rules for $250. He knocked out eleven men during the tour.

In Sullivan's era, no formal boxing titles existed. He became a champion after defeating Paddy Ryan in Mississippi City, near Gulfport, Mississippi, on February 7, 1882. Modern authorities have retroactively labelled Ryan the "Heavyweight Champion of America", but any claim to Ryan's being a "world champion" would have been dubious; he had never contended internationally as Sullivan had.

Depending on the modern authority, Sullivan was first considered world heavyweight champion either in 1888 when he fought Charley Mitchell in France, or in 1889 when he knocked out Jake Kilrain in round 75 of a scheduled 80-round bout. Arguably the real first World Heavyweight champion was Jem Mace, who defeated Tom Allen in 1870 at Kenner, Louisiana, but strong anti-British sentiment within the mostly Irish American boxing community of the time chose to disregard him.[citation needed]

When the modern authorities refer to the "heavyweight championship of the world," they are likely referring to the championship belt presented to Sullivan in Boston on August 8, 1887. The belt was inscribed Presented to the Champion of Champions, John L. Sullivan, by the Citizens of the United States. Its centerpiece featured the flags of the US, Ireland, and the United Kingdom.

Mitchell came from Birmingham, England and fought Sullivan in 1883, knocking him down in the first round. Their third meeting took place in 1888 on the grounds of a chateau at Chantilly, France, with the fight held in driving rain. It went on for more than two hours, and by the end of the bout, both men were unrecognizable and had suffered so much damage that neither could lift his arms up to punch. Both men couldn't continue, and the contest was considered a draw.

At this point, the local gendarmerie arrived and arrested Mitchell. He was confined to jail for a few days and later fined by the local magistrate,[citation needed] because bare-knuckled boxing was illegal in France at the time.[citation needed] Swathed in bandages, Sullivan was helped to evade the law and taken across the English Channel to spend the next few weeks convalescing in Liverpool.

Charley Mitchell fight

[edit]In March of 1888, Sullivan fought Charley Mitchell, an English prize-fighter, for 39 rounds; it was a draw. [7]

The Kilrain fight

[edit]

The Kilrain fight is considered to be a turning point in boxing history because it was the last world title bout fought under the London Prize Ring Rules, and therefore was the last-ever bare-knuckle heavyweight title bout. It was also one of the first sporting events in the United States to receive national press coverage.

For the first time, newspapers carried extensive pre-fight coverage which included reporting on the fighters' training and speculating on where the bout would take place. The traditional center of bare-knuckle fighting was New Orleans, but the governor of Louisiana had forbidden the fight in that state. Sullivan had trained for months in Belfast, New York, under trainer William Muldoon, whose biggest problem had been keeping Sullivan from liquor. A report on Sullivan's training regimen in Belfast was written by famed reporter Nellie Bly and published in the New York World.[8]

Rochester reporter Arch Merrill commented that occasionally Sullivan would "escape" from his guard. In Belfast village, the cry was heard, "John L. is loose again! Send for Muldoon!" Muldoon would snatch the champ away from the bar and take him back to their training camp.[citation needed]

On July 4, 1889, one Kentucky newspaper stated: "The Sullivan-Kilrain prize fight which is to take place in Louisiana on next Monday is now the most talked-about event in sporting circles."[9] The stakes were $20,000 and a diamond world championship belt.[10]

On July 8, 1889, an estimated 3,000 spectators boarded special trains for the secret location, which turned out to be Richburg, a town just south of Hattiesburg, Mississippi. The fight began at 10:30, and at first it looked like Sullivan was going to lose. "The first fall and first blood were awarded to Kilrain, but the first knock-down was accomplished by Sullivan," reported one newspaper. "Kilrain failed to knock Sullivan down at all."[11] Sullivan vomited during the 44th round. However, the champion got his second wind and was able to turn things around for himself. After a grueling beatdown, Kilrain's manager finally threw in the towel after the 75th round.

The Governor of Mississippi offered a $1,000 reward for each fighter.[12]

Today, a historical marker is located at the site of the fight, just off Interstate 59, and the fight is immortalized by the Sullivan-Kilrain Road which runs through the site of the event, at the corner of Richburg Road.

Later career

[edit]

Sullivan did not defend his title for the next three years. During this period, he was a friend and supporter of Irish boxer Ike Weir, who became America's first Featherweight boxing champion in 1889. Both Weir and Sullivan were Boston natives, and Sullivan occasionally appeared at Weir's bouts.

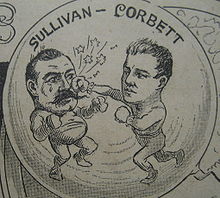

Sullivan agreed to defend his title in 1892, against challenger "Gentleman Jim" Corbett. The match was on September 7 in New Orleans.[13] It began at 9 p.m. in the electrically illuminated Olympic Club in the upper Ninth Ward neighborhood now known as Bywater section. The venue filled to its 10,000-person capacity despite hefty ticket prices ranging from $5 to $15 (approximately $142 to $426 in 2020). The heavyweight contest occurred under the Marquess of Queensberry Rules, but it was neither the first title fight under those rules nor was it the first title fight using boxing gloves. Corbett was younger and faster, and his boxing technique enabled him to dodge Sullivan's crouch and rush style. In the 21st round, Corbett landed a smashing left "audible throughout the house" that put Sullivan down for good. Sullivan was counted out and Corbett was then declared the new champion. When Sullivan was able to get back to his feet, he announced to the crowd the following: "If I had to get licked, I'm glad I was licked by an American".[14]

In 1895 Sullivan and Paddy Ryan joined the touring company of the musical The Wicklow Postman, and presented exhibition boxing matches prior to performances of the play.[15]

Sullivan is considered the last bare-knuckle champion because no champion after him fought bare-knuckled. However, Sullivan had fought with gloves under the Marquess of Queensberry Rules as early as 1880 and he only fought bare-knuckled three times in his entire career (Ryan 1882, Mitchell 1888, and Kilrain 1889). His bare-knuckle image was created because his infrequent fights from 1888 up to the Corbett fight in 1892 had been bare-knucklers.

Sullivan retired to Abington, Massachusetts, but appeared in several exhibitions over the next 12 years, including a three-rounder against Tom Sharkey and a final two-rounder against Jim McCormick in 1905 in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He continued his various careers outside boxing such as being a stage actor, speaker, celebrity baseball umpire, sports reporter, and bar owner. In his later years, Sullivan also gave up his lifelong addiction to alcohol and became a prohibition lecturer.[16]

Death

[edit]The effects of prize fighting along with his being overweight and unhealthy after a long life of overindulging in food and alcohol took its toll on the boxer. Like most boxers of the time, he did not live a very long life. Sullivan died at age 59 at his home in Abington, Massachusetts, supposedly from heart disease.[17] At the time of his death, Sullivan had a young boy named Willie Kelly in his custody. The priest of Sullivan's church had brought Kelly, an orphan, to the front of the parish and encouraged anyone with the means to care for the boy to do so.[17] Sullivan is buried in the Old Calvary Cemetery in Roslindale, a neighborhood of Boston. He died with 10 dollars in his pocket (equivalent to almost $180 in 2018). According to the county where Sullivan died he had an estate worth $3,675.

Legacy

[edit]Sullivan was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990, as a member of the hall's original class.[18] He had a record of 47 wins, 1 loss and 2 draws, with 38 wins by knockout, though many sources disagree on his exact record.

The barn where Sullivan trained still stands in the small town of Belfast, New York, and is now the Bare Knuckle Boxing Hall of Fame.[19]

Sullivan and Corbett's landmark 1892 fight is depicted in the 1942 Warner Brothers biopic Gentleman Jim, a fictionalized account of their relationship. Ward Bond portrayed Sullivan alternately as a fiery peacock of a heavyweight champion and, after his title loss, as a sweet, sentimental good sport. Sixteen years later, actor Roy Jenson played Sullivan in the 1958 episode, "The Gambler and the Lady", of the syndicated television anthology series, Death Valley Days, hosted by Stanley Andrews. In the story line, Sullivan in his tour of local communities across the country fights an exposition match against Buck Jarrico (Hal Baylor). When the prize money designated to refurbish the school goes missing, both the teacher, Ruth Stewart (Kathleen Case), and the gambler, Brad Forrester (Mark Dana), are falsely accused based on appearances.[20][unreliable source?]

On their 2017 album Life Is Good, the band Flogging Molly made reference to Sullivan on the track 'The Hand of John L. Sullivan'.

Professional boxing record

[edit]| 51 fights | 47 wins | 1 loss |

|---|---|---|

| By knockout | 38 | 1 |

| By decision | 8 | 0 |

| By disqualification | 1 | 0 |

| Draws | 2 | |

| No contests | 1 | |

| No. | Result | Record | Opponent | Type | Round, time | Date | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 51 | Loss | 47–1–2 (1) | James J. Corbett | KO | 21, 1:30 | Sep 7, 1892 | Olympic Club, New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. | Lost world heavyweight title (American version); Marquess of Queensberry Rules |

| 50 | Win | 47–0–2 (1) | Jake Kilrain | KO | 75 (?) | Jul 8, 1889 | Richburg, Mississippi, U.S. | Retained world bare-knuckle heavyweight title; Won inaugural world heavyweight title (National Police Gazette);[21] London Prize Ring Rules |

| 49 | Draw | 46–0–2 (1) | Charlie Mitchell | PTS | 39 | Mar 10, 1888 | Chantilly, Oise, France | Retained world bare-knuckle heavyweight title; London Prize Ring Rules |

| 48 | Win | 46–0–1 (1) | William Samuells | TKO | 3 (3) | Jan 5, 1888 | Philharmonic Hall, Cardiff, Wales | |

| 47 | Draw | 45–0–1 (1) | Patsy Cardiff | PTS | 6 | Jan 18, 1887 | Washington Roller Rink, Minneapolis, Minnesota U.S. | |

| 46 | Win | 45–0 (1) | Paddy Ryan | KO | 3 (?) | Nov 13, 1886 | Mechanic's Pavilion San Francisco, California, U.S. | |

| 45 | Win | 44–0 (1) | Frank Herald | TD | 2 (?) | Sep 18, 1886 | Coliseum Rink, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. | Agreement on a decision of police intervened |

| 44 | Win | 43–0 (1) | Dominick McCaffrey | PTS | 7 (6) | Aug 29, 1885 | Chester Driving Park, Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. | Won inaugural world heavyweight title; Marquess of Queensberry Rules; accidentally fought a 7th round |

| 43 | Win | 42–0 (1) | Jack Burke | PTS | 5 | Jun 13, 1885 | Driving Park, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

| 42 | NC | 41–0 (1) | Paddy Ryan | NC | 1 (4) | Jan 19, 1885 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 41 | Win | 41–0 | Alf Greenfield | PTS | 4 | Jan 12, 1885 | Institute Hall, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 40 | Win | 40–0 | Alf Greenfield | TD | 2 (?) | Nov 18, 1884 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 39 | Win | 39–0 | John Laflin | KO | 4 (?) | Nov 10, 1884 | New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 38 | Win | 38–0 | Enos Phillips | KO | 4 (?)0 | May 2, 1884 | Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. | |

| 37 | Win | 37–0 | William Fleming | KO | 1 (4) | May 1, 1884 | Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. | |

| 36 | Win | 36–0 | Dan Henry | KO | 1 (4) | Apr 29, 1884 | Hot Springs, Arkansas, U.S. | |

| 35 | Win | 35–0 | Al Marx | KO | 1 (4), 0:55 | Apr 10, 1884 | Grand Opera House, Galveston, Texas, U.S. | |

| 34 | Win | 34–0 | George M Robinson | DQ | 4 (4) | Mar 6, 1884 | Mechanic's Pavilion San Francisco, California, U.S. | |

| 33 | Win | 33–0 | Boiquet | KO | 1 (?) | Feb 1884 | Victoria, British Columbia, U.S. | |

| 32 | Win | 32–0 | James Lang | KO | 1 (4) | Feb 6, 1884 | Seattle, Washington, U.S. | |

| 31 | Win | 31–0 | Sylvester Le Gouriff | KO | 1 (4) | Feb 1, 1884 | Astoria, Oregon, U.S. | |

| 30 | Win | 30–0 | Fred Robinson | KO | 2 (?) | Jan 12, 1884 | Butte, Montana, U.S. | |

| 29 | Win | 29–0 | Jeff Tomkins | KO | 1 (?) | Jan 1884 | Butte, Montana, U.S. | |

| 28 | Win | 28–0 | Mike Sheehan | TKO | 1 (?) | Dec 4, 1883 | Davenport, Iowa, U.S. | |

| 27 | Win | 27–0 | Morris Hefey | KO | 1 (?) | Nov 26, 1883 | Saint Paul, Minnesota, U.S. | |

| 26 | Win | 26–0 | Jim Miles | TKO | 1 (?) | Nov 3, 1883 | East St. Louis, Illinois, U.S. | |

| 25 | Win | 25–0 | James McCoy | TKO | 1 (?) | Oct 17, 1883 | McKeesport, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 24 | Win | 24–0 | Herbert Slade | TKO | 3 (4) | Aug 6, 1883 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 23 | Win | 23–0 | Charlie Mitchell | TKO | 3 (?) | May 14, 1883 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 22 | Win | 22–0 | Harry Gilman | KO | 3 (?) | Jan 25, 1883 | Toronto, Ontario, Canada | |

| 21 | Win | 21–0 | P J Rentzler | TKO | 1 (4) | Nov 17, 1882 | Theatre Comique, Tacoma, Washington, U.S. | |

| 20 | Win | 20–0 | Charley O'Donnell | KO | 1 (?) | Oct 30, 1882 | Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

| 19 | Win | 19–0 | S P Stockton | KO | 2 (?) | Oct 16, 1882 | Fort Wayne, Indiana, U.S. | |

| 18 | Win | 18–0 | Henry Higgins | TKO | 3 (4) | Sep 23, 1882 | St. James Athletic Club, Buffalo, New York, U.S. | |

| 17 | Win | 17–0 | Joe Collins | PTS | 4 | Jul 17, 1882 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 16 | Win | 16–0 | Jimmy Elliott | KO | 3 (?) | Jul 4, 1882 | Brooklyn, New York, U.S. | |

| 15 | Win | 15–0 | John McDermont | TKO | 3 (?) | Apr 20, 1882 | Grand Opera House, Rochester, New Hampshire, U.S. | |

| 14 | Win | 14–0 | Paddy Ryan | RTD | 9 (?) | Feb 7, 1882 | Mississippi City, Mississippi, U.S. | Won American bare-knuckle heavyweight title; London Prize Ring Rules |

| 13 | Win | 13–0 | Jack Burns | KO | 1 (4) | Sep 3, 1881 | Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

| 12 | Win | 12–0 | Captain James Dalton | KO | 4 (4) | Aug 13, 1881 | Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

| 11 | Win | 12–0 | Dan McCarty | KO | 1 (?) | Jul 21, 1881 | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 10 | Win | 10–0 | Fred Crossley | KO | 1 (4) | Jul 11, 1881 | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 9 | Win | 9–0 | John Flood | KO | 8 (?) | May 16, 1881 | Yonkers, New York, U.S. | |

| 8 | Win | 8–0 | Steve Taylor | TKO | 2 (4) | Mar 31, 1881 | Harry Hill's, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 7 | Win | 7–0 | Professor John Donaldson | RTD | 10 (?) | Dec 24, 1880 | Pacific Garden, Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. | London Prize Ring Rules |

| 6 | Win | 6–0 | George Rooke | KO | 3 (?) | Jun 28, 1879 | Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 5 | Win | 5–0 | John A. Hogan | PTS | 4 | 1879 | Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 4 | Win | 4–0 | Tommy Chandler | PTS | 4 | 1879 | Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 3 | Win | 3–0 | Dan Dwyer | TKO | 3 (?) | Jun 28, 1879 | Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 2 | Win | 2–0 | Johnny Cocky Woods | KO | 5 (?) | Mar 14, 1879 | Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 1 | Win | 1–0 | Jack Curley | KO | ? (?), (1:14:00) | Mar 13, 1879 | Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | Fight to the finish; Show began on the 13th. Fight began on the 14th at 1am |

Screen portrayals

[edit]George Walsh portrayed John L. Sullivan in the 1933 film The Bowery.

John Kelly portrayed John L. Sullivan in the 1942 film My Gal Sal.

Ward Bond portrayed John L. Sullivan in the 1942 film Gentleman Jim.

Greg McClure portrayed John L. Sullivan in the 1945 film The Great John L..

Roy Jenson portrayed John L. Sullivan in the 1958 episode "The Gambler and the Lady" of the television series Death Valley Days.

Claude Akins portrayed John L. Sullivan in the 1961 episode "The Hand that Shook the Hand" of the television series Tales of Wells Fargo.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "BoxRec: John L Sullivan". BoxRec. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ In This Corner — John L. Sullivan with comments by Bert Sugar.

- ^ "John L. Sullivan | American boxer". May 24, 2023.

- ^ "Sports: Breaking Records, Breaking Barriers | John L. Sullivan | Smithsonian's National Museum of American History |". March 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "The Champion Slugger: John L. Sullivan Tells the Story of His Life to a Denver Reporter," Denver Tribune, reprinted in the Chicago Inter-Ocean, Jan. 1, 1884, pg. 16.

- ^ "Tombstone, Arizona: Boxing In The Wild West (1880–84)". cyberboxingzone.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ^ "The Big Sandy news. [volume] (Louisa, Ky.) 1885-1929, March 15, 1888, Image 2". Big Sandy News (Louisa, KY). March 15, 1888. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ Bly, Nellie (May 26, 1889). "A Visit with John L. Sullivan". New York World. Archived from the original on August 18, 2014. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ^ "The Big Sandy news. [volume] (Louisa, Ky.) 1885-1929, July 04, 1889, Image 2". Big Sandy News (Louisa, KY). July 4, 1889. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ "The Big Sandy news. [volume] (Louisa, Ky.) 1885-1929, July 11, 1889, Image 2". Big Sandy News (Louisa, KY). July 11, 1889. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ "The Big Sandy news. [volume] (Louisa, Ky.) 1885-1929, July 11, 1889, Image 2". Big Sandy News (Louisa, KY). July 11, 1889. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ "The Big Sandy news. [volume] (Louisa, Ky.) 1885-1929, July 18, 1889, Image 2". Big Sandy News (Louisa, KY). July 18, 1889. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ Wood, Peter (April 22, 2015). "Strong Boy—The Life and Times of John L. Sullivan, America's First Sports Hero". boxing.com. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016.

- ^ Corbett was King of a New Era Archived September 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Christopher Klein (2013). Strong Boy: The Life and Times of John L. Sullivan, America's First Sports Hero. Lyons Press. p. 236. ISBN 9781493001989.

- ^ "Sullivan on Temperance; Ex-Pugllist Says He Wasted $500,000 Through Liquor". The New York Times. August 2, 1915. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Strong Boy Blog: The Final Hours of John L. Sullivan". February 2, 2014.

- ^ "John L. Sullivan". International Boxing Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 13, 2011.

- ^ Whirty, Ryan (October 20, 2010). "Belfast, N.Y., houses Bare Knuckle Hall". ESPN. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ "The Gambler and the Lady on Death Valley Days". IMDb. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ Police Gazette Sporting Annual 1918

Further reading

[edit]- Isenberg, Michael T. John L. Sullivan and His America (University of Illinois Press, 1994.)

- Pollack, Adam J. John L. Sullivan: The Career of the First Gloved Heavyweight Champion (McFarland, 2015)

- Reel, Guy. "Richard Fox, John L. Sullivan, and the rise of modern American prize fighting." Journalism History 27.2 (2001): 73+

- Sullivan, John L. Article in The Washington Post, 30 July 1905. "'Your hands are too big; you'll never make a boxer,' was one of the bits of discouragement passed to me when I was beginning to attract notice as a puncher. That was the popular notion at that time, because Sayers, Heenan, Yankee Sullivan, and some other good men who had made their tally and passed up had small hands."

External links

[edit]- Boxing record for John L. Sullivan from BoxRec (registration required)

- ESPN.com

- Boxing Hall of Fame

- The Boston Strongboy

- Yesterday's News An 1883 newspaper account of a Sullivan exhibition in St. Paul, Minn.

- Clarence W. Rowley Papers Relating to Buffalo Bill and John L. Sullivan. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- John L. Sullivan at IMDb

- 1858 births

- 1918 deaths

- American male boxers

- American people of Irish descent

- American bare-knuckle boxers

- Boxers from Boston

- Drinking establishment owners

- Heavyweight boxers

- International Boxing Hall of Fame inductees

- People associated with physical culture

- People from South End, Boston

- World heavyweight boxing champions